Defects of empirical knowledge have less to do with the ways we go wrong in philosophy than with defects of character: such things as the simple inability to shut up; determi- nation to be thought deep; hunger for power; fear, especially the fear of an indifferent universe.

—David Stove (1990)

2.1 THE ENVIRONMENTALIST WORLDVIEW

Recently, a couple of cheerful, but nevertheless gravely serious, Greenpeace fundraisers came to my door asking if they could count on my monetary help in Greenpeace’s struggle to “save the planet.” When I asked what the planet needed to be saved from, they almost rolled their eyes at my woeful ignorance, and began to recite solemnly the litany of humankind’s environmental sins, which, to be frank, I had already heard many times before: extinctions of species; destruction of habitat; increasingly dangerous levels of toxins in the air, the soil, the water, and mothers’ milk; glowing dumps of nuclear wastes—in short, the defilement of Earth. To hear them, you would think that we should all be in bed, sick from the poisons we had been eating and breathing, and that nothing but ashes, smoke, and drizzling toxic rain should be visible outside.1

In fact, the suburb where I live is green, the trees are plentiful and filled with squirrels and birds (including owls, hawks, goshawks, and Steller’s jays), and after dark the deer and raccoons wander and raid people’s gardens. My suburb is not very special in this regard. The return of wild species to the cityscape is not unique to my city but a common feature of many North American and European cities these days. I have been in suburbs in three continents that have more or less as many trees, squirrels, fields, rabbits, walking trails, birds, and bird-watchers as mine does. The streams, brooks, and waterfronts in most urban areas have been restored from their sorry state a few decades ago, when they were apt to be used as sewers or dumps, so the return of wildlife includes fish as well as mammals and birds.

“It looks nice,” the female said, “but it’s not natural. What you see around you is not a natural environment. Anyway, it’s not sustainable. We owe it to future generations to leave them a world that they can actually survive in, not a toxic wasteland. We are literally killing the planet.”

“Suburbia is an illusion,” he added. “It all runs on fossil fuels, which we can’t keep burning forever. It’s all got to come crashing down sometime. We’ll be extremely lucky to make it to the middle of the century.” I agreed that it did seem unlikely to me that we would still be burning gasoline in our cars in 50 years’ time (mind you, I was picturing technological progress, not environmental collapse).

“Well, perhaps then, you would like to help us combat the environmental crisis,” they said, hopefully. The belief that the environment is in a state of crisis is the most common article of faith among environmentalists. The title of a recent book by a distinguished biologist, Niles Eldredge (1998), shows what I mean: Life in the Balance: Humanity and the Biodiversity Crisis. In Time to Change, a biologist and television-environmentalist advocate, David Suzuki (1994), repeatedly uses the phrase “environmental crisis.” This list could be extended indefinitely,∗ but there is no need. If you are an environmentalist, you will take it as given that the world is in an environmental crisis.

They said the crisis was urgent, and I invited them inside to tell me more. Of course, I had heard about the environmental crisis before. It was a concept that became popular after the publication by the best-selling environmental book ever, The Limits to Growth (Meadows 1972). This book of the Club of Rome, which sold some 30 million copies worldwide in some 30 languages, created a sensation when it was published in 1972. I remembered reading it with some alarm years before either of my fundraisers had been born. It had employed MIT-designed computer models (which in those days automatically implied scientific authority) to forecast the future of the planet. The future it predicted was dire: massive environmental degradation, undrinkable water, unbreathable air, unproductive farmland, illness, famine, despair. All of this was supposed to have come to pass well before the end of the century.2

I could not help but think that the urgency of the environmental crisis had a time scale unlike any we have seen before. It is continuous, ongoing urgency, ongoing for decades, in fact.3 Although environmental apocalypse is upon us, or has even over- taken us, the crunch always remains in the near, but unspecified, future. This is a form of urgency that cheats the test of time. We are reminded here of old movies in which the heroine is tied to the railway tracks, screaming, while the train rushes up to her—over and over again. For nearly half a century, at least since Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), we have been told to repent, that the end is nigh—told, in fact, that we are already in the very midst of the final destruction—and yet things have not gotten worse.

How could I begin to talk with these Greenpeace fundraisers when they believed in a crisis that they had never seen? Suspecting that their concern for the environment might perhaps be the expression of concern for themselves, I suggested that instead of saving the planet from us, maybe they should really worry about saving us from the planet.4

“When the planet gets tired of us,” I said, “it will just brush us off like this,” and I made the motion of brushing a crumb off my sleeve. I was thinking of the many species that had been removed from the face of the Earth before us. All it took was a new plague, a new global ice age,5 or a comet racing toward us from the Oort cloud.

“No,” they said, the planet would never hurt us, although we hurt it continually. They explained that the environment was naturally balanced and that only our species upset this balance of nature. Nature itself, they reassured me, was wisely benign toward every organism in the environment. The environment was intrinsically good, and would do good, and only good, if it were not for us environmentally wicked humans. Yet some 20 meters away from these petitioners were outcroppings of the scarred rocks which all over the midlatitudes of our planet bear mute testimony to the last ice age. Compared to it, all the works of man, all of our environmental effects since we were spawned by evolution, pale to insignificance. During the ice ages, forest and field, lake and marsh, were frozen solid and bulldozed south, the soil itself scoured off the surface of the ground, and the very rocks below deeply scarred. Environmentalists talk about environmental destruction and yet seem not to have heard about the ice ages. The miles-thick crust of ice actually weighed large portions of Earth’s land surface itself below sea level (as it still does in parts of Antarctica and Greenland). It is quite likely that the glaciers will return and that the ponds and meadows and forests around us will be utterly destroyed, along with all of the animals that now make their homes in those ponds, meadows, and forests. The planet will brush us off—again.

“You must have heard about global greenhouse warming! That’s something we’re doing to the planet. It’s not doing it to us.” They launched into an explanation of the basic principles of the scientific model: We use fossil fuels, this releases carbon dioxide (CO2) into the air, and CO2 acts like the glass walls of a greenhouse, letting in the pure white light of the Sun while trapping the red light that Earth would otherwise excrete into outer space, warming the planet disastrously. I knew from experience that it would have been pointless to explain that greenhouses do not work by tapping infrared radiation but by interrupting circulation. That was a long story, and these people were too busy to spend that much time on someone like me, who was obviously an environmental dinosaur. They said gravely that unless we stopped using oil and coal, disaster upon disaster would descend upon not only us, but that millions of others species would be doomed to extinction. “Extinction is forever,” she reminded me. Then she said the glaciers would melt and the seas would rise up to flood New York, London, Hong Kong, and Rio de Janeiro, along with great swathes of Bangladesh, wiping out millions of the poorest, most desperate people on the planet.

It would have seemed callous to interrupt them in their solemn delivery of this grave warning, but it seemed that they were laboring under the false impression created by Al Gore’s film An Inconvenient Truth. In that film Gore shows coastal cities flooding under 30 feet of water, implying (although never saying) that this would be the immediate result of global warming—but the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC),6 the environmentalists’ own recognized authority on the theory of greenhouse warming, had predicted only an 8-inch rise in sea level (20 cm plus or minus 10 cm) by 2100 (IPCC 2007a, p. 812, Fig. 10.31). An 8-inch rise in sea level does not spell disaster—it barely spells nuisance. In fact, this is less than an inch per century above the background rate of sea rise over the last few centuries (Hancock and Hayne 1996), so global warming has a negligible effect on sea-level rise.

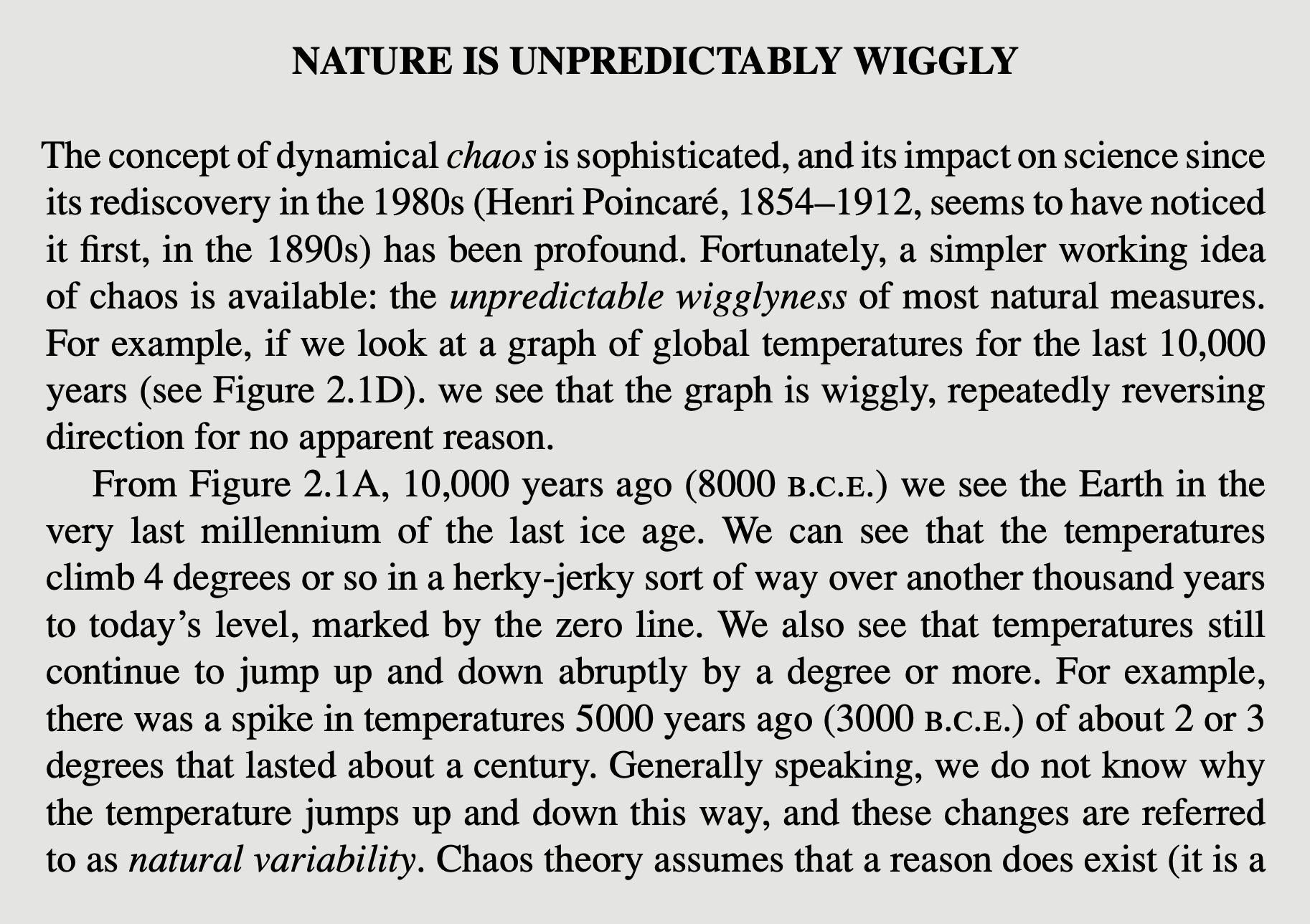

Nor did I mention that for all we know, once again according to the IPCC itself, adding CO2 to the air might actually result in half as much warming, or no warming, of the planet, as the IPCC itself admits. The IPCC states very clearly in its famed Third Assessment Report7 that Earth’s climate is “inherently chaotic” (IPCC 2001a, p.773).8 In a chaotic system,the IPCC said, “there are feedbacks that could potentially switch sign” (ibid.). What this means is that something which normally has one sort of effect may suddenly have the opposite effect. Since the warming itself was a feedback of the increasing CO2, it followed that it, too, could even switch sign and so cause cooling rather than warming. In other words, global temperature is unpredictably wiggly—the signature of chaos in action. Indeed, nature as a whole, as revealed in all of its various measures, is unpredictably wiggly. Predicting the weather next week was difficult enough—what made anyone think that they could predict climate a century in advance? This was conceivable, but it hardly seemed likely. Could it possibly be well advised to stop using fossil fuels, and bring the economy to a virtual halt, on the basis of such a risky prediction?

Anyway, according to the IPCC’s own predictions, even if we were to stop the use of fossil fuels within a few decades, this would have only a negligible effect on global warming in the next century: It would reduce by half a degree the warming of 3◦F (2◦C) predicted by 2100. Besides, it seemed quite unlikely to me that 100 years from now we would still be using mainly fossil fuels. In 1900, people still relied on horses for transportation and oxen for agriculture, while a century later they were jetting around the skies. Surely we should expect just as much change in the next 100 years as in the last. But I didn’t get a chance to mention any of this, for my Greenpeace guests had moved on to predict terrible hurricanes that would “devastate” the world.

“Have you heard about Chris Landsea?” I asked. They had not.

“Haven’t you heard of the Sixth Extinction?” my environmentalist fundraisers demanded. Indeed, I had, but according to the rules of polite conversation I had learned as a child, it was my turn to speak.

“Chris Landsea resigned from the IPCC because he believes that it has become politicized. He was their expert on hurricanes, and he concluded, as hurricane experts generally have, that global warming has only a tiny effect on hurricanes. The fellow in charge of writing the IPCC reports ignored his own experts, and instead gave interviews saying that global warming will cause hurricanes to become more intense, and that the very large number of hurricanes in recent years was due to anthropogenic greenhouse gases. Landsea repeatedly told him and the IPCC that this was not true—but they ignored him. So he was forced to resign.”9

They sat silently, looking at me resentfully, as though a bad smell had been released into the room—as though the very idea that hurricanes would not devastate the world was unwelcome.

“It’s all on the web,” I said. “You can read it for yourself. Landsea made a formal statement.”

“There is an overwhelming scientific consensus when it comes to climate change,” the male Greenpeace member said.

“He must be funded by a multinational corporation with a vested interest in dumping megatons of carbon into the atmosphere,” she chimed in.

My heart sank. I had often come to this point before with bright young environmentalists like these. They were good people, people who were ready, willing, and able to work for the greater good—which they took to be raising money for Greenpeace. I knew from the case of my own children that people of their age are taught environmentalist values and theories all the way through school. Their science texts and social studies texts lamented the environmental crisis, and professed environmentalist values as necessary to avoid environmental apocalypse. I recalled school projects in which my kids were instructed that the only sustainable form of human life would, in effect, repeal the industrial revolution. Farms would be small; no human-made fertilizers or pesticides would be used; only horses and oxen would be used for plowing and harvesting; people would live in small houses; cities would also be small, since population would be controlled and more people would have to live in the country to produce the needed food; long-distance trade would disappear; people would eat only local foods and use only local goods—and every person, animal, and plant would be happy, and every day would be sunny and bright. There were also villains in these lessons, and they were always impersonal: business, greed, and the dreaded “multinationals.”

My Greenpeace alms-gatherers were automatically certain that anyone who doubted any part of the environmentalist doctrines they had absorbed as small children was a “denier” and probably in the service of dark powers such as the multinationals. They swiftly convicted deniers of falsehood because they were (supposedly) always funded by some (unspecified) multinational group with an interest in environmental issues. They did not realize that they had just falsely accused me of an intellectual crime, and they did not see the irony that they themselves were collecting money for a well-known multinational group with an interest in environmental issues and an annual budget of hundreds of millions of dollars, which it devotes solely to the pro- motion of its interests (not to mention the salaries of its executives and employees). Their minds were made up, their convictions enclosed completely in rhetorical armor. I asked them if they would look up Chris Landsea on the Internet. I might as well have asked them to start smoking. They looked at each other, and with a tacit nod, switched gears into a mode that I suspect had been taught them by their Greenpeace leaders as the proper move at this point.

“Well, it’s obvious that you have a differing point of view,” he said.

“Yes,” she said, “we have to agree to disagree, and leave it at that.” And so they headed for the door.

Environmentalism is a complex phenomenon, and not all environmentalists have the same views on every environmental issue. However, there are strong family resemblances among them. Mary Jones may have the Jones blue eyes and cheerfulness, while John Jones has the Jones chin and height, so that John and Mary are clearly Joneses although they do not share resemblances with each other. Similarly, each environmentalist shares enough characteristics with the others that his or her membership in the environmentalist family is clear. The principal set of environmental family resemblances seem to be these: that our form of life is unsustainable; that we are endangering life in general with our pollution; that our use of fossil fuels will cause runaway global warming; that we are causing a sixth great extinction; that we have upset the balance of nature—and that all of these things amount to an urgent environmental crisis.

2.2 IS THERE AN ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS?

This is a very big question, but it seems that the onus is clearly on the environmentalist here. Obviously, we affect nature. Like any other species, we live by constant interaction with nature. Since our population is about to peak within a couple of generations (see Figure I.1 in the Introduction), our effect is unsurprisingly large at this point. But effect and harm are distinct. They are not the same. Peace and prosperity are at record highs right now, as is environmental awareness. Environmentalists are asking us to change our way of life radically: that is the intended effect of accept- ing their claim that there is an environmental crisis. Since acceptance of the claim would have such a disruptive effect, it is not to be taken lightly. Indeed, the claim of environmental crisis should be accepted only if the evidence for it is undeniable and its consequences grave, for the simple reason that changing our way of life radically would itself undeniably have grave consequences.

There is no way to settle this issue in a few pages, but we can begin to shine a light into some of the corners. The environmental crisis that environmentalists describe is the sum of a number of problems of various sorts: environmental, social, ethical, evaluative, and philosophical. We can hope to at most touch on the most important of these in the following pages. One of these, global warming, is so important, so timely, so complex that merely outlining the issues will require a thorough discussion, which we take up in Case Study 7.

Let’s begin with pollution. How bad is it? In one of the worst cases of London smog, in December 1952, 4000 people met their untimely demise in just seven days (Lomborg 2001, p. 164). Will those days return?

Yes: In industrialized countries, allergies, asthma, and cancer have increased in recent decades, a sign of increasing pollution despite society’s half-hearted efforts to control it. In newly industrializing countries such as China and the reindustrializing countries of the former USSR, where even the half-measures of the industrialized countries have not been taken, pollution is rampant. Pollution does not respect national boundaries, and in the absence of international laws cannot be controlled.

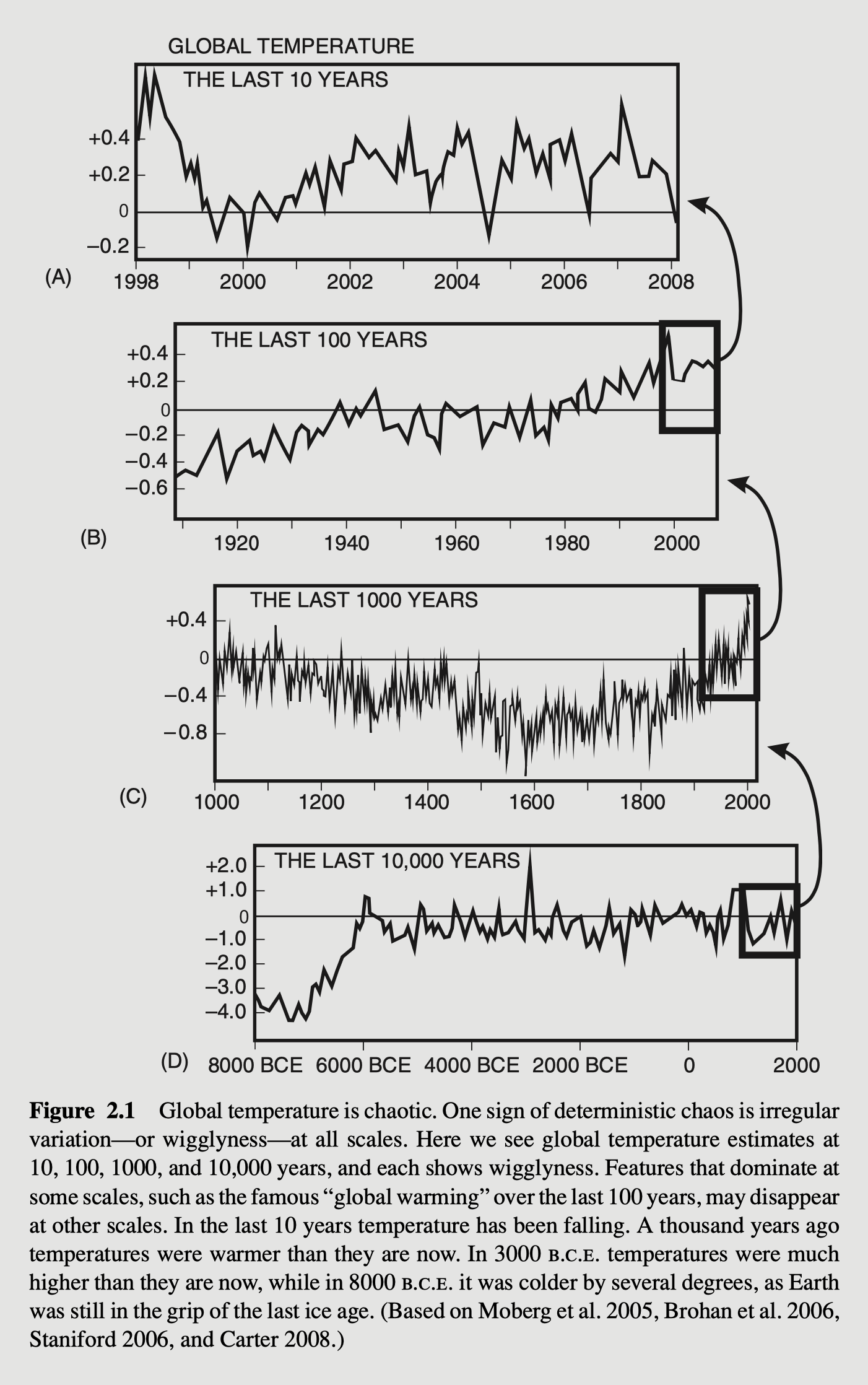

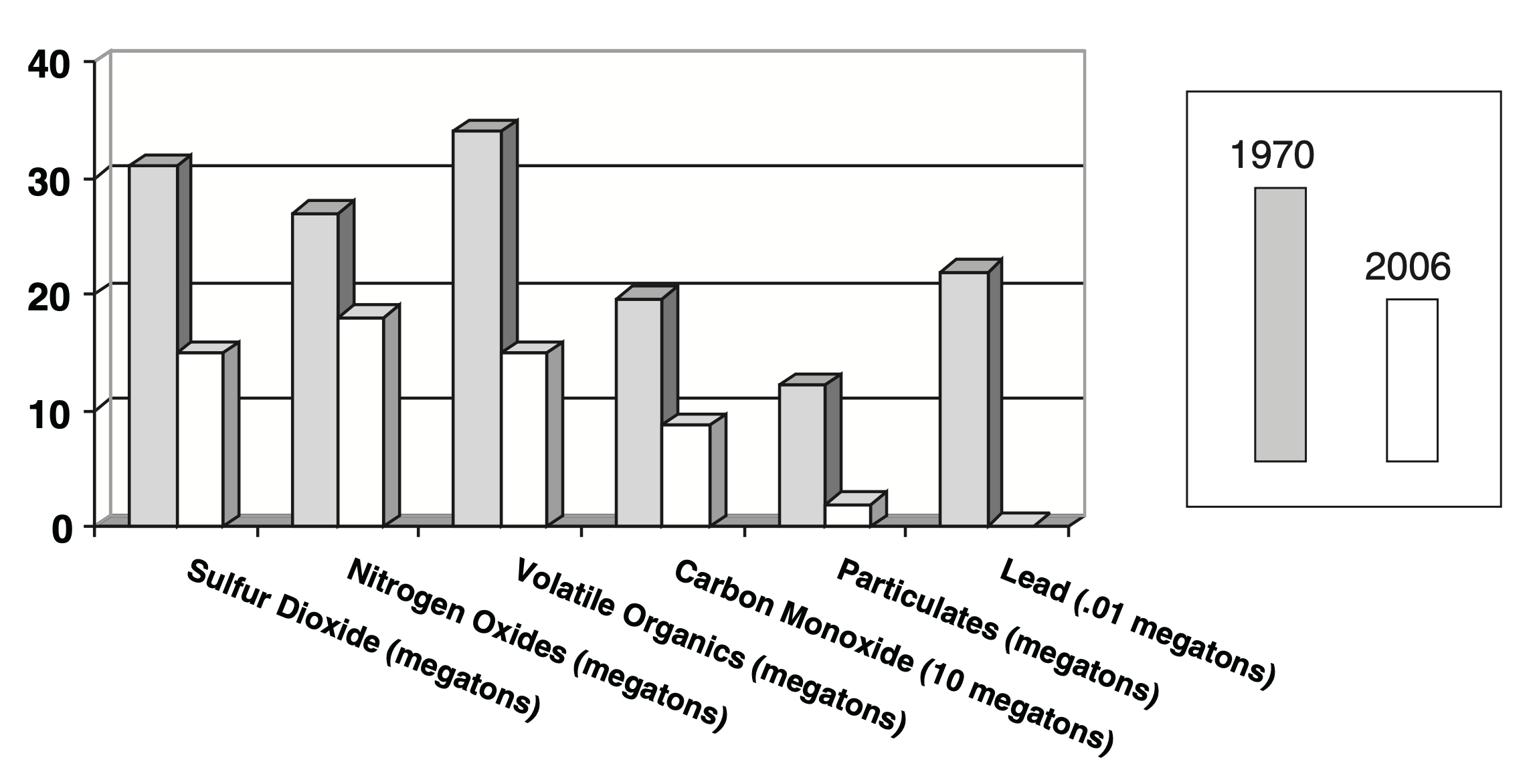

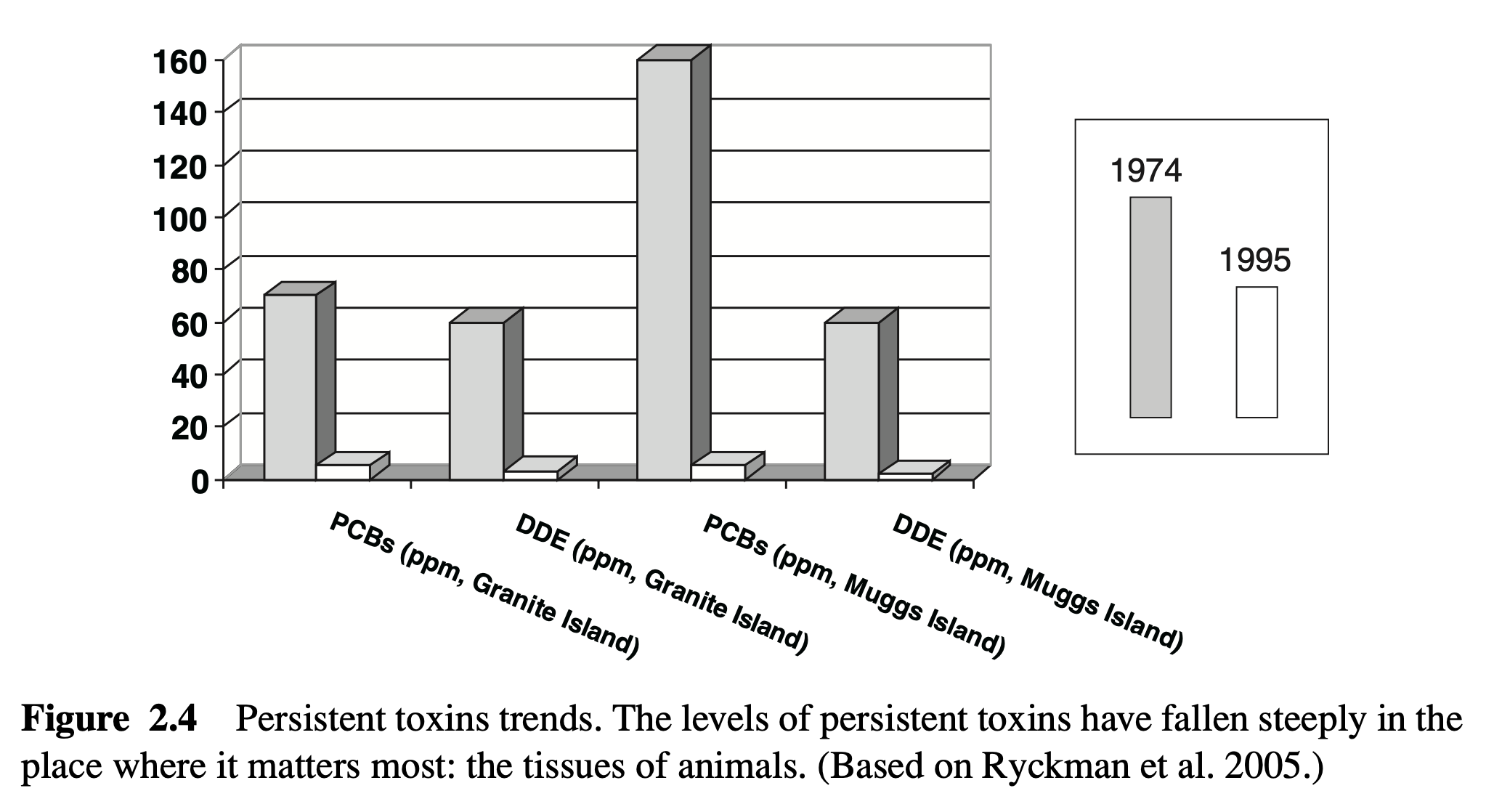

No: There is plenty of evidence that the trend in pollution is definitely downward. This is definitely true of air pollution, as can be seen in Figure 2.2. This graph is based on U.S. data, but they are typical of the developed nations. This graph considers the criteria pollutants as they are called, since they are the most toxic for life in general. Emissions of all of the criteria pollutants are trending downward and are generally at less than half their levels a few decades ago. The worst of them, lead, has been reduced the most, some 95% or so. In addition, countless measurements and constant monitoring show that the reduction in emissions has reduced their levels in the atmosphere as well, as shown in Figure 2.3.10

Perhaps most significant of all is the evidence that shows the levels of pollutants are decreasing in the bodies of animals as well, as exemplified in Figure 2.4. This graph tracks the trend of a very troubling sort of pollutant, the persistent toxin, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and DDE (the metabolic product of DDT in the body) in the bodies of animals living in the wild (Granite Island is near the north shore of Lake Superior) and in a highly industrialized area (Muggs Island is in Lake Ontario next to Toronto in the midst of the industrialized northeast corner of the United States). Toxins in the bodies of living things is ultimately what our concern about pollution is all about, so it is very reassuring that these levels have fallen so steeply. It is noteworthy that these measurements are of herring gulls, which are high in the food chain. Since they are at the top of a long complex food chain, toxins concentrate in their food and thus in their bodies, magnifying the ambient levels thousands of times. The fact that the levels of these persistent toxins has fallen so far and so fast tells us that the ambient levels of these substances must have fallen even farther than these graphs show. It is nice to know that our efforts to control the release of these substances has been so effective. It is also nice to be reminded just how robust and resilient nature can be.

So we can rest assured that when it comes to pollution, things are getting better, not worse, for ourselves and other living things, especially in the most developed nations. As for the increase in cancer rates, that is merely the downside of the fact that people are living longer. The cause of the increase in asthma and allergies is not known, but we do know it is not higher pollution levels, since the main increase is in the industrialized world, where pollution levels are down, not up.

Common Ground: More needs to be done, even in industrialized nations, since the levels of many pollutants are still harmful for humans and other living things, especially in cities during weather that provides poor air circulation. We do want to see the trend lines continue downward. Also, these data do not apply to industrializing nations, where pollution is greater than in the United States and even increasing. Something should be done about this. We should work to ensure that growing prosperity will lead to a higher level of environmental awareness (the second stage; see Section 1.5) as it did in the industrialized world.

One important aspect of the downward trend of pollution in the industrialized world is that it was achieved during an unprecedented rise in population, prosperity, and health. This counts against the environmentalist opinion that modern industrialized life is unsustainable. There is pretty persuasive evidence that human beings have caused massive species loss and habitat loss both in their hunter-gatherer form of life and in their preindustrial agricultural form. If that is true, the only thing that ever reversed our species’ historical tendency to harm nature has been environmental standards within the context of increasingly sophisticated industrial methods. In any case, it is clear that we can improve environmental standards even as we improve our own health and happiness.

Do environmentalists dare accept this good news? Clearly, environmentalists take a very dim view of modern industrialized society. If this is because they think it is unsustainable, they should take a brighter view if it really is sustainable after all. If they do not, why not? Obviously, the belief in environmental crisis is crucial in pragmatic terms for maintaining the momentum of the environmentalist agenda and of the environmentalist establishment, including institutions such as Greenpeace. Certainly, we do not want to slide into complacency, but a steady state of alarm will eventually pall and the credibility of environmental concerns—as well as the credibility of environmentalism and environmentalist institutions—will be undermined. So to maintain morale and sow the seeds of agreement among all parties, we might consider the following points:

- We are often told that industry is implacably opposed to any environmental programs since they cut into profits, that science (which gets over 90% of its funding from industrial sponsors) must follow suit, and that government cannot stand up against this coalition of interests, all of which stalls the fight against pollution. However, the production of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) has been phased out via the Montreal Protocol (1987). This was achieved by extensive consultation and cooperation among governments, scientists, and industries. Unless we assume that the success of the protocol is illusory, we are forced to conclude that these key groups can have a shared interest in working for the good of nature.

- Over the last five decades the massive loss of forests due to acid rain has been predicted continually. However, the amount of forested land in the United States has remained steady since 1920, even as its population, agricultural production, and industrial production all increased dramatically (USDA 2000, p. 2). Only small losses of forest to acid rain have ever been documented. Unless we assume that acid rain is not a serious threat to forests, we are forced to conclude that the programs undertaken to reduce acid rain have been effective, and the progress reported in the statistical measures of the sort we have seen is indeed real.

- We have often been warned that ongoing pollution threatens us with the collapse of agriculture. However, a few generations ago, chronic malnutrition afflicted more than half of the world’s population, whereas only a tiny proportion of humanity now faces this problem, even though population has more than doubled during the same period. The reason: Agricultural production has grown even faster than population. Unless we assume that pollution is not a serious threat to agriculture, we must conclude (1) that pollution has indeed been de- creasing in the industrialized world, and (2) that there is still time to reverse the trend of increasing pollution in other parts of the world.

- We have often heard dire predictions that toxic substances building up in the environment, in the air we breath, the water we drink, and the food we eat will result in an epidemic of disease and death. Fortunately, the average lifespan continues to grow, especially in the most industrialized countries. Unless we assume that pollution is not a serious threat to our health, we may conclude that pollution has indeed been decreasing in the industrialized world.

Let us turn now to the environmentalist belief that human beings have upset the balance of nature. This presumes that the balance of nature exists in the first place. However, although it is a central idea in popular environmentalists and still has some resonance even among environmental scientists, it has been officially rejected by biological science for some time. Nature is now generally recognized by scientists to be chaotic. As we have seen, the IPCC itself recognizes that the climate is chaotic, and it is difficult to see how climate could be chaotic without introducing chaos into the entire natural system.

Indeed, it now seems that evolution itself stagnates without nature’s unpredictable changes. During long periods of natural stability, organisms become highly, even overly, adapted to local conditions, and thus more susceptible to harm given any sudden change. A plant that has genetically adapted to a precise range of temperatures will be less able to handle a sudden change of temperature than one that has adapted to a less stable regime. The great extinction events of the past seem to have been required for evolutionary progress. The dinosaurs ruled Earth for some 180 million years, an almost unimaginable span of time for ephemeral creatures such as us, whose species did not even exist much more than 100,000 years ago. The dinosaurs might have ruled forever were it not for natural chaos. As always, the disruption of natural stability caused a new blossoming of evolution, including the rise of mammals, including us.

Despite the apparent evolutionary necessity for unpredictable changes, environ- mentalists do not like them. Indeed, they ignore the beneficial effects of previous extinction events both large and small, and universally loathe any current species extinctions. It seems likely, therefore, that this environmentalist attitude is motivated not by biological science as such, but by rather personal affection for the current life-forms and ecosystems—a heartfelt biological conservatism, as it were. As we shall see in more detail in Chapter 5, environmental science has adopted and promotes a number of environmental values, of which the loathing of extinction is but one. However, regardless of the scientific status of the value, whether positive or negative, of species extinction, most of us would certainly be disturbed if we really were in the midst of a sixth great extinction event.

There have been five great extinction events in the past,11 each involving loss of 20 to 50% of all species. The sixth great extinction (6thX) is supposed to be a human-caused loss of species that is just as massive. Niles Eldredge says: “As long ago as 1993, Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson estimated that Earth is currently losing something on the order of 30,000 species per year—which breaks down to the even more daunting statistic of some three species per hour. Some biologists have begun to feel that this biodiversity crisis—this ‘Sixth Extinction’—is even more severe, and more imminent, than Wilson had supposed” (Eldredge 2001). He goes on to say: “We can divide the Sixth Extinction into two discrete phases. Phase One began when the first modern humans began to disperse to different parts of the world about 100,000 years ago. Phase Two began about 10,000 years ago when humans turned to agriculture” (ibid.). Thus, 6thX is supposed to be a (1) rapid and massive extinction caused by humans that (2) began very long ago, and (3) is now accelerating. Is 6th X real?

No: The most relevant core of the doctrine for the environmentalist, point 3), is the claim that we are currently causing a massive acceleration in species extinction. This claim has a history of exaggerations that quickly ran aground on actual events. In 1979, the prestigious Norman Myers12 estimated that 40,000 species became extinct every year (Myers 1979), and his number quickly became accepted wisdom among environmentalists. If Myers had been right, a million species would have disappeared by now, about 10 to 20% of all the species on Earth (scientific estimates of the total number of species are themselves pliable, with the most widely accepted numbers falling around the 5 million range). Thomas Lovejoy agreed: “Of the 3 to 10 million species now present on the earth, at least 500,000 to 600,000 will be extinguished during the next two decades” (Ray et al. 1993).13 Clearly nothing like this has hap- pened; we could not help but notice if it had. Paul Ehrlich (1988) predicted a loss of up to 250,000 species per year over the same period, which would have resulted in the disappearance of 50 to 100% (!) of all species by now. E. O. Wilson still estimates 27,000 to 100,000 extinctions per annum. Meyers, ignoring his previous, and apparently false, prediction that some 800,000 extinctions should already have occurred, still boldly predicts a loss of up to “one-third to two-thirds of all species now extant” within the “foreseeable future” (a rather vague temporal parameter from a scientific point of view; Myers and Knoll 2001). David Suzuki can claim to be the voice of moderation here, “Every year at least 20,000 species disappear forever, and the rate of extinction is speeding up” (1994, pp. 18–19), despite the absence of evidence for his conjecture.

Yes: These forecasts are based on known rates of habitat destruction, known densities of species in the various habitats that are being destroyed, and known sensitivities of these species to habitat loss. Most of the species are little known and do not appear on nature programs on television, so their loss is not being observed and documented. It does not follow that it is not occurring.

No: The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) maintains a database called the IUCN Red List (which is available online14). It lists a grand total of 684 extinctions since year 1500.15 Examination of this list reveals the sorry history of humans hunting various species out of existence. Most of the extinctions have occurred on islands, where local variants of pigs, ducks, squirrels, and so on, became recognized biological species. Because they were restricted to a small terrain, humans were able to hunt and kill every one of them. The rate of this sort of extinction has gone down steeply. Indeed, the Red List has catalogued only the tail end of a round of extinctions caused by human beings, one that climaxed with firearms and growing human populations, and has since subsided due to the environmental awakening of Homo sapiens. In fact, between 2004 and 2006, the Red List shows no extinctions at all—not one. So the evidence is clearly against point 3: Species loss is decelerating, not accelerating. In addition, no one ever suggested a massive extinction event 100,000 years ago. There is simply no evidence of any such thing. So the data are against point 2 as well.

Yes: There is a huge scientific literature in which various models of habitat-loss extinction are developed. Close examinations of relatively small areas of tropical rain forest will often reveal a very large number of species of plants and animals, some of which may never have been scientifically cataloged. Models can then take measures of the amount of tropical forest cleared annually to calculate loss of species.16 The models employ the concept of the keystone species, which if lost, as experiments have shown, cause further losses to other species. Resulting models show that species are connected to each other like the strands of a delicate spider web, so that after a few strands are cut, the other strands also fall.

No: Of course, if you picture the life on this planet as a delicate web, your scientific theory will predict that it will behave like a delicate web and will collapse under very slight stress. Models can only show what your assumptions entail; they cannot show that your assumptions are correct. Only observation can tell us that. The observations tell a very different story, however. About 1.4 million species have been catalogued, and it is usually estimated that something like 10 times that many actually exist, say 10 to 20 million species. Since 684 extinctions have been observed in 507 years, even if we ignore the recent fall in the numbers of extinctions observed, we have observed fewer than two extinctions per annum. Even if we suppose that the actual number of extinctions might be 100 times as large as the number observed, it will still take tens of thousands of years for the proportion of species lost to approach that of the least of the great extinctions.

The fifth great extinction event, the one that killed off the dinosaurs, is thought to have been caused by a huge comet or meteorite striking Earth (Alvarez 1997), causing an explosion equivalent to billions of atomic bombs. That event was horrific to a degree we can barely comprehend. In the twinkling of an eye the atmosphere turned to fire, the ground heaved and opened in a global earthquake, and the sun was blotted out. Millions of species were lost within days. What, then, are we to make of such 6thX claims as the following? “Sixty-five million years ago that extraterrestrial impact—through its sheer explosive power, followed immediately by its injections of so much debris into the upper reaches of the atmosphere that global temperatures plummeted and, most critically, photosynthesis was severely inhibited—wreaked havoc on the living systems of Earth. That is precisely what human beings are doing to the planet right now” (Eldredge 2001). Precisely? Surely Eldredge is not using the word in its scientific sense. Hyperbole is not precision.

In summary, 6thX seems to be an exaggeration. Since the scientific data do not support 6thX, it is hardly surprising that the 6thX scientific literature bases it on models rather than or observation. Scientific theories are supposed to be based on evidence, but in the case of 6thX, they are based on yet more theory, as illustrated in Eldredge’s presentation of 6thX above.17

2.3 OUR EMOTIONAL ENVIRONMENT

Should we be in a state of alarm about nature? It is an old joke that when the world fails to end on the prophesied date, prophets of doom simply regroup to name a later date. Unfortunately, when scientists engage in this maneuver, they give us promissory note science instead of real science. The prestigious New York Times, informed by environmentalist scientists, reported in 1991 (October 10) that rising seas caused by global warming would drive millions of people from their homes by 2000. This, of course, never happened. And when it did not, the same scientists still warned that oceans will rise, and soon. But the oceans did not rise; instead, the prediction descended, at a very impressive rate, until it now rests at some 8 inches over the next century. This initial rapid exaggeration of danger, followed by a much slower surrender of our sense of alarm, is very human, very biological—and scientists are, after all, both human and biological. We have been equipped by evolution with the ability to anticipate bits of the future, because this has improved our potential to survive and reproduce. It is perfectly natural, then, that we instinctively become alarmed at perceived dangers, and only reluctantly let go of our sense of alarm. Better safe than sorry is the rule.

But if environmental apocalypse hasn’t arrived yet, how long should we sustain our state of environmental alarm? How long can an imminent disaster be expected before we may conclude that it isn’t really imminent? Our emotions have evolved to handle situations on a much shorter time scale than the changes that we have produced within nature in the past or can produce in the future. Since the environmental crisis is defined as being of our own making, it will not be sudden, like a meteor impact, but gradual, like the growth of civilization itself. Its time scale will also be orders of magnitude greater than our emotions are designed to accommodate. Does it really make sense for us to be alarmed—much less panicked?

To begin with the obvious, nature is in no danger whatever of being destroyed—at least not by us. It seems a bit ludicrous that this even has to be pointed out, but so many people accept the idea of the destruction of the environment, its devastation, complete collapse, and so on, that ludicrous or not, a few words must be said to lay this bogeyman to rest. Ever since Alvarez (1997) and others have shown beyond the shadow of a reasonable doubt that the era of the dinosaurs was brought to an end by a comet or meteorite striking the Earth in a cataclysmic impact, it has been clear that Earth’s life is a very tough customer indeed. Cataclysmic changes are thought to be behind many, if not most, of the major species extinction events in the past, and there were many, including the five great extinctions. If repeated strikes by bolides (as these extraterrestrial bombshells are called) did not destroy Earth’s life, we certainly will not. The history of Earth is full of catastrophic events: not just bolide impacts, but such things as 100-fold increases in cosmic rays as our solar system cycled through the spiral arms of the Milky Way galaxy, and the darkening of the sun as it encountered clouds of interstellar dust. These dire events have a cheerful lesson to teach us: The complex network of living creatures is not easily damaged, and when it is damaged, the many strands that remain regenerate a new net that is richer and more sophisticated than before.

The word fragile is almost always used to describe the environment. We are not to think of nature as a resilient network, but as a tenuous web. We are not to walk confidently on the face of Earth, but instead tentatively, apologetically, and fearfully. Environmentalists want us to see Earth’s life as a house of cards, ready to topple given the least disturbance. But nothing could be farther from the truth. In many cases, their arguments employ equivocation between sensitivity and fragility. Living nature is sensitive—but sensitivity is a completely different thing from fragility. For example, a tiger is sensitive—it can sense things that would escape our notice entirely—but it is not fragile. Sensitivity is the capacity to respond to very subtle inputs. Yes, living nature is sensitive. It responds to the most subtle of inputs—often in very subtle and sophisticated ways. But sophistication of response is proof of resilience—the very opposite of fragility.

It is now undeniably clear that our dear Earth, our planet, our home, has survived dozens of crises, such as extraterrestrial impacts or massive climate change, with its precious cargo, the spark of life, intact. Life is tenacious, tough, adaptable, like the grass that inevitably springs up in cracks in the pavement. We now know that living things populate not only the land and the sea, but that extremophiles (Madigan and Morris 1997, D. Roberts 1998, Lubick 2002), as they are called, live in volcanic craters, under glaciers, even thousands of feet underneath the rocky crust of our beautiful Earth. Not one of the cataclysms experienced to date has been sufficient to remove all of the larger plants and animals, or even to threaten the extremophiles. Of course, the Alvarez event was horrible, and although not all flesh and flora were destroyed by it, we would never tolerate any action by our fellow human beings that would bring about anything remotely like it. Yet this positive fact must nevertheless be admitted: There is nothing that humankind could do, even if all of our bombs and poisons and slash-and-burn farmers were unleashed at once—and surely, more important, nothing that we will do—that would approximate what nature itself did in the Alvarez event.

Environmentalists should also meditate on the last ice age, to truly become conscious of the perpetual change of the environment, the incredible scale of these changes, and the fact that they are still going on—not with the sudden impact of a meteorite but at a pace difficult for creatures as ephemerally brief as human beings to notice. The last ice age (the last in a series of dozens of ice ages) is said to have come to an end a mere 7000 years ago, a twinkling of an eye in the 3.5-billion year history of life. We should also keep in mind that we have no reason to believe that the series of ice ages came to an end with the last period of glaciation. The glaciers are still retreating from the last ice age, and we are in the midst of an interglacial period, a sort of summer in a cycle of seasons on a geological time scale. In fact, summer has lingered unseasonably long.

Much as we may unconsciously drift toward the pleasant view that the ice ages are over, aided and abetted by our scientific doubts concerning the mechanism that causes them,18 simple scientific induction tells us that another ice age is coming. Indeed, over the past few millions of years, ice ages have dominated the climatic picture. Interglacials have been brief, in the range of 10,000 to 20,000 years, while the ice ages last for hundreds of thousands of years. Our current interglacial is reckoned to be 11,500 years old, about the length of the previous interglacial some 200,000 years ago. If this oft-repeated pattern is to be repeated, we are already on the brink of the next ice age. But soon or late, the next ice age is highly probable, and so is all the damage it will cause to living nature. Ice ages are not cataclysmic events such as meteor impacts but simply one stage in a very much slower cycle. Nevertheless, they cause enormous damage to living nature. Figure 4.1 (p. 60) is a snapshot of ice-age devastation.

Environmentalists may protest that since the ice age is natural, its effects cannot be called damage—but that is logically inconsistent. If human beings caused the same destruction of life and habitat, it would indeed be considered not just damage, but a travesty.

There was a time when it seemed reasonable to think that, just maybe, the tropical ecosystem remained intact during periods of glaciation, but we now know that this was not the case. Although paleometeorological and paleobiological studies of the Brazilian jungle and jungles in similar latitudes are yet fairly primitive, it does seem that the equatorial rain forests, just like the temperate ones, come and go with the cycle of ice ages. Although more study is needed to provide a really clear picture, the lands where the equatorial jungles now sit were much cooler and dryer during the long periods of ice. During those periods the plants and animals that now populate the more northerly temperate zones and highlands in and around the jungles moved to dominate the jungle areas themselves (see, e.g., N. Roberts 1998, pp. 73, 105).

Where did the countless jungle species go? Where did the corals and tropical warm-water fishes go? The fossil evidence indicates that many, perhaps most, were simply wiped out by cold and drought. Since there are far more species in the tropics than in more polar zones, we can only conclude that enormous numbers of species became extinct. The evidence also indicates that pockets of these tropical species survived, perhaps in rather different forms, and in smaller eco-niches, adapted to the then-prevailing conditions, in a manner similar to that in which temperate species become adapted to live at the treelines in high altitudes or high latitudes. It would seem that natural selection has favored plants and animals that have the ability to evolve rapidly, that is, to adapt over a few generations to changing conditions, such as periodic ice ages. But this much is certain: If past ice ages did not wipe them out, then, certainly, today’s slash-and-burn farmers will not.

Have a little faith in nature—and in humankind!

- Interestingly enough, a few years earlier some other Greenpeace fundraisers had sought money explicitly for the Greenpeace campaign to prevent nuclear testing by the French in the Muroroa Atoll in the South Pacific. I had then asked whether they thought preventing the French test would stabilize or destabilize the global balance of nuclear weapons and whether, therefore, it would increase or decrease the probability of nuclear war. They replied that Greenpeace had no political goals, and that its only concern was the good of the environment. When I suggested that Greenpeace’s hindering of the French was inevitably political and must have political consequences, they were unmoved. Nuclear testing was bad for the environment, and that was good enough for them: Nuclear testing had to be stopped. They were sure that anything that was good for the environment would, as if guided by an invisible hand, work for the greater good politically, economically, socially. As unbelievable as this is once it is expressed plainly, the notion that environmental values magically transcend all other values is nevertheless a common article of faith for environmentalists. We return to this issue in Chapter 3. ↩

- The follow-up book, Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse (Meadows et al. 1993), does not back away from the apparently false predictions of its predecessor, which, if they had come true, would have been obvious. Instead, it takes the view that the limits to growth can be passed without any obvious results, at least at first, just as a wild population of deer, say, can “overshoot” the limits of its grazing area without any obvious sign of danger, only to be decimated by a disastrous famine later on. Plausible or not, this transformation of global collapse from an observable to a theoretical state does constitute a stark change from the first report. To reaffirm the urgency of the environmental crisis, a third book has also been published in this series (Meadows et al. 2004). ↩

- The following title from the prestigious journal Science is poignant in this regard: “Conservation: Tactics for a Constant Crisis” (Soule ́ 1991). ↩

- Expression of fear and concern for humankind, particularly “future generations,” is also a staple concept of environmentalism. It is a very unstable concept for environmentalists: as we shall see in more detail in a later chapter, there is an antihuman element in environmentalism as well. Since we are the sole source of environmental harm, it would be better for the environment if we did not exist. Since environmentalists’ guiding ideal is the good of the environment, they must see their own species in a very unflattering light. The following book title expresses another concept that is common among environmentalists: Nature’s Revenge (Johnson et al. 2006). The idea is that nature will give us grief, and that we deserve whatever we get: Nature will be getting vengeance, we will be getting our just deserts. ↩

- The evidence is mounting that once or twice the entire Earth has been covered by glaciers in extreme ice-age conditions. ↩

- The IPCC is the scientific body created by the United Nations that has been warning the world about Global Greenhouse Warming and recommending immediate implementation of the Kyoto protocols to reduce the use of fossil fuels. ↩

- This report is famous because in it the IPCC said that due to advances in climate modeling during the five years since its previous report, it had finally concluded that we human beings were the cause of the recent warming trend, mainly via our use of fossil fuels. ↩

- This is the statement made by the IPCC in its Third Assessment Report: “The climate system is particularly challenging since it is known that components in the system are inherently chaotic; there are feedbacks that could potentially switch sign, and there are central processes that affect the system in a complicated, non-linear manner” (IPCC 2001, Section 14.2.2, Predictability in a Chaotic System, p. 773). It is vitally important to fully realize that the chaotic nature of climate is an inherent, hence inescapable, characteristic of climate, and one that renders prediction difficult in principle: “These complex, chaotic, non-linear dynamics are an inherent aspect of the climate system. As the IPCC WGI Second Assessment Report…has previously noted, “future unexpected, large and rapid climate system changes (as have occurred in the past) are, by their nature, difficult to predict” (ibid.). How difficult? It is impossible to say, precisely. In fact, it is quite possible that any prediction, no matter how certain it may seem, could be completely wrong: “This implies that future climate changes may also involve ‘surprises’. . . . these arise from the non-linear, chaotic nature of the climate system” (ibid.). In short (and as we shall see in more detail in what follows), we know on scientific grounds that we cannot know quite what the climate will do or why. ↩

- Landsea’s stated reason for resigning from the IPCC was “the misrepresentation of climate science while invoking the authority of the IPCC” by Dr. Trenberth, “Lead Author responsible for preparing the text on hurricanes” for the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, along with the fact that “the IPCC leadership dismissed my concerns when I brought up the misrepresentation” (Landsea 2005). He points out that (1) “any impact in the future from global warming upon hurricanes will likely be quite small” (by 2100, assuming that global warming occurs as predicted, “hurricanes may have winds and rainfall about 5% more intense than today”); (2) “even this tiny change may be an exaggeration;” and (3) amazingly, the IPCC had admitted these conclusions in its previous reports. He concludes, on the basis of a lengthy interchange with the IPCC leadership (which he also made public), that it has, at least in part, “become politicized.” As I will argue in Chapter 5, environmental science was the product of an environmentalist agenda from the start, so always had an element of political advocacy, inasmuch as it calls for action in the political domain. ↩

- Figures 2.2 and 2.3 are based upon U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data (EPA 2006, and EPA 2007a through EPA 2007g). ↩

- The five great (actual) extinctions occurred at the ends of the following eras: the Ordovician [440 million years ago (mya)], the Devonian (370 mya), the Permian (270 mya), the Triassic (245 mya), and the Cretacious (65 mya). ↩

- Myers’ website at Oxford University begins with a list of his political appointments: “. . . scientific consultant and policy adviser to the White House, U.S. Departments of State and Defense, NASA, the World Bank, seven United Nations agencies, and the European Commission.” It then goes on to list his administrative appointments in bodies that direct science and the arts: “He is a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the World Academy of Art and Science, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Royal Society of Arts.” Finally, there is reference to his scientific achievements: “Dr. Myers is the originator of the biodiversity ‘hotspots’ strategy, which has generated over $300 million for conservation activities,” assuming that his “strategy” is a scientific achievement. Internet: http://www.green.ox.ac.uk/fellows.htm#Myers (15 March, 2004). ↩

- See http://www.nationalcenter.org/dos7127.htm (March 15, 2004). ↩

- http://www.iucnredlist.org (August 16, 2007). ↩

- Of the extinct species, 260 are snails, 69 are insects, and 74 are mammals. ↩

- For an example, see E. O. Wilson’s calculation leading to an estimated extinction rate of 27,000 species per year just within tropical forests (1992, p. 280). One cannot help but be awed by Wilson’s confidence as he recreates the complex factors involved by means of complex formulas. ↩

- For the scientist, a model is not an observable entity in the world but one through which the world is observed. Whereas one looks at a model airplane in the same way that one looks at the airplane of which it is a model, the scientist looks through his or her model at the things it models. For this reason, scientists will often confidently accept their own models even when others do not, for they see the evidence itself through the model. Of course, scientists will fight like tigers for their own models (or theories, as they are also known), a vital tendency which ensures that the model gets a chance to grow, develop, overcome hurdles, and show its potential. But it is the facts, not the fight, that determine whether a model is correct. ↩

- The most popular theory among scientists was first proposed persuasively by Milankovitch (1941): Changes in Earth’s axial tilt in relation to its orbital eccentricity and the seasons cause the sequence of ice ages via alterations in solar heating (distance and angle), a theory that is typically called orbital forcing. Still, other theories, such as solar variability and changes in ocean currents, have their loyal supporters. The main problem with orbital forcing is that it should have been at work for billions of years, but the cycle of ice ages has appeared only during the last few millions of years, far less than 1% of the total. So some other mechanism is needed to support the orbital forcing hypothesis, and about this there is no general agreement. In fact, the Sun is supposed to have increased in brightness by some 30% since Earth was formed. The rapidity of the temperature changes involved in ice ages is another problem, since orbital changes are extremely gradual. Still, these and other problems are generally discounted given the generally good temporal agreement between orbital forcing and the ice ages. ↩