One impulse from a vernal wood/ May teach you more of man,/ Of moral evil and of good,/ Than all the sages can.// Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;/ Our meddling intellect/ Misshapes the beauteous forms of things—/ We murder to dissect// Enough of Science and of Art,/ Close up those barren leaves;/ Come forth, and bring with you a heart/ That watches and receives.

—William Wordsworth (1798a)

Many years ago, my 9-year-old brother Bob showed me something he held hidden in his hand. It was a tiny robin. It had a badly broken leg and seemed on the verge of losing consciousness. I can still see the dull look in its eyes and the tears in Bob’s. He had saved it from some kids who were about to kill it, and now he desperately wanted it to survive. He had an exaggerated opinion of my powers, since I had attained the august age of 12. We dug up some worms in the garden, but the robin would not even look at them. It had decided to shut out the world. I had a sinking feeling, but could not give up. We finally managed to put a bit of bread soaked in milk into its beak. It just sat there, motionless, while bubbles formed around its nostrils, and a drop of milk ran down its throat. Then it swallowed—and everything took a turn for the better. It ate quite a lot of bread soaked in milk, and then switched without difficulty to worms the next day. Already it seemed happy as could be, wiggling his wings and opening his beak anytime a hand approached him. Or was it her? We never knew.

I put his tiny leg in a tiny matchstick splint the first night, but could not fix his foot. His thumb claw stayed limp and folded under his toe claws. But this was a peppy little animal, and soon he was hopping around and perching without any trouble. We have videotape copies of dad’s home movies of the robin, begging for food as baby birds do, eating worms in the garden as we dug them up, and taking a bath in a bowl of water that our mom had thoughtfully provided. He lived in an old birdcage in the house, which we would put on the back porch every day so he could be outside with us. We would leave the cage door open so he could hop out, or when he was older, fly out. He would leave on his own and return when he felt like it. Once we were eating lunch outside in the back yard while the robin begged for bits of food. Suddenly a pair of robins made an angry scolding attack on us in a determined effort to rescue this little bird. We were amazed. The idea that these birds were his parents seemed farfetched. He had been rescued a half-mile away, after all. But, parents or not, this pair of shrieking robins made a much more fearsome attack than you might think, and we retreated to see what would happen. The adult birds seemed agitated, while our little robin was perfectly calm. Clearly, there was some sort of communication going on between them. But in the end they left quietly, and he stayed with us.

Eventually, he began to sing the strangely evocative song that robins sing at dawn, answering the robins outside from his cage in the house. He began to sound and look like a proper robin. He turned from a hungry, mottled pudge-ball into a sleek, swift, sassy, sharp-beaked bird. He instinctively knew how to hunt worms—he seemed to listen for them to surface, and when one did he just hopped over and fiercely tugged it out of the ground. Given his uncanny skill, there was no need to dig worms any more. So he got his own meals while I guarded against cats. His flying became stronger, and his forays from the cage became longer. The last time I saw him, he was sitting high in a poplar tree with another robin that he had, apparently, befriended. That night he did not return to his cage on the back porch. We never saw him again. For a few years I checked every robin I saw for a crook in its right leg, but was always disappointed. We never did give him a name.

My family’s rescue of this bird was, from a rational point of view, very strange behavior. What advantage could we possibly find in rescuing a bird? No other species of animal would ever have saved that bird. Why did we? It makes evolutionary sense for animals to act altruistically toward members of their own species, since that increases their species’ fitness. But being Good Samaritans toward members of other species must then reduce fitness. The Good Samaritan himself might have scolded us for wasting our time helping a bird instead of a person. What evolutionary quirk might lead Homo sapiens to undermine its fitness by spending its time and energy on members of other species? Obviously, a 9-year-old boy does not have a mothering instinct that is triggered by small birds. So what made him shelter the bird in his own hands?

If you feel that questions like this one can only be answered by the heart, not the head, then you have a romantic side. If you feel that the heart’s answer to the question is more or less obvious, you are inclined toward the romantic side. If you feel that anyone that has a heart would never ask a question like this in the first place (especially in the presence of children), you may well be a full-blown romantic. What is a romantic? There is no explicit definition, no set of words that captures all, and only, romantics. Romantics must surely see this as poetic justice, since they believe that real life escapes the analytic cuts and synthetic fences that intellectuals use to divide and conquer it. The romantic soul is free, and the proof of this is that it will not submit to analysis or be hedged in. Nevertheless, despite the lack of a generally accepted definition, there is general agreement that there was a romantic movement in Europe and North America in the first half of the nineteenth century. It is also generally accepted that there is a romantic way of looking at things, a romantic philosophy, a romantic “take” on the world as a whole and human life as a whole. It is even generally accepted that a person of romantic temperament (i.e., whose personal philosophy is romantic) will understand why a couple of boys would rescue a robin, bind its wounds, nurse it back to health, and set it free.

8.1 ENVIRONMENTALISM AND ROMANCE

You cannot understand environmentalism (nor yourself if you are an environmentalist) unless you understand romance and the romantic, and you cannot fully sympathize with environmentalism unless you have a romantic side. Most people do have a romantic side, of course, and so most people can fully sympathize with environmentalists. Environmentalism is a modern echo of a strand of romanticism that has run through human cultures since pagan times. In particular, the roots of the environmentalist idea of humankind’s proper relationship with nature can be traced back to that of the romantics. At the very least, there is a large and significant overlap between environmentation and romance, as I hope to show briefly in this chapter.1

The environmentalist ideal is not a nice apartment in the city, but a simple cabin in the woods. Environmentalists want to reduce their impact on nature. They want to make themselves smaller, not larger, when it comes to the natural world. They wish they lived in simpler times, with simpler problems, simpler joys, simpler values—before their biological kindred abused and subdued the Earth. There was a time, they believe, when Homo sapiens lived in harmony with nature, in small kinship bands. Environmentalists believe in the noble savage, at least in principle. The “noble savage,” the untamed human being, is capable of every sort of virtue that the civilized human being is capable of: bravery, loyalty, love, creativity, intelligence. Virtue does not depend on analysis, but something deeper: human sympathy, the ability to imagine yourself in the other person’s place, the need to protect the weak . . . in a word, the human heart. Civilization puts pavement between the human heart and the natural world that gave birth to it, and to which it answers. Human nature itself has been cut off from its roots and has gone bad in the cities, with their violence, drugs, and various forms of perverse behavior. So-called “primitive” people may not have been able to make nuclear weapons, but their inner nature hummed in tune with nature outside. They were free.

I cannot say whether every environmentalist will accept this characterization. They too, are free. No doubt there are some who prefer a more scientific idiom. Science is certainly more authoritative than poetry in any case, and to that extent useful for environmentalism. Even scientists, however, will agree that in the nineteenth century there was something called “the” romantic movement, in which nature and the concept of the noble savage captured the popular imagination. Scholars tell us that there were various romantic movements in various places as romanticism waxed and waned through history, but I think that a good case can be made for thinking that “the” romantic movement of the nineteenth century was special: It rose up in reaction to the most intense wave of industrialization that the world had seen up to that time. The steam engine appeared in 1712 and then in 1763 was launched by James Watt on a long course of improvements that continue to the present day. It replaced muscle power, so it replaced people and animals. Unemployed people went to the cities looking for work, along with the animals’ unemployed breeders, keepers, and handlers, launching a wave of urbanization that continues to the present day. In 1764, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, a machine that would replace spinners of yarns and threads. In 1768, a bunch of spinners wrecked a bunch of his machines in a doomed attempt to avert their impending unemployment. We might, with considerable justice, date the start of the romantic revolution to that historical event.

Romanticism was the poetic revolution that inspired and traveled along with the industrial counterrevolution.2 By the time the Luddites were squaring off against the British Army in 1811, the major English romantic poets—Byron, Coleridge, Shelley, and Wordsworth—were sweeping away the poetic competition with their love of nature, their love of common folk, and their rejection not just of what Blake called “the dark Satanic mills” of industry, but of the science—and the scientific intellect—that gave birth to it. The Luddites’ industrial counterrevolution was doomed; its leaders were to meet their end on the gallows, but romanticism conquered the hearts of Europeans even as the factories won their minds and pocketbooks. Romantic poetry, novels, plays, opera, music, dance, and painting dominated the media of the times. Architecture returned to the time before the industrial revolution and even before the scientific revolution that made it possible: the age of King Arthur, Lancelot, Robin Hood, and Friar Tuck. Medieval castles and churches were restored by Violet le Duc, part of a massive medieval revival in architecture. Gothic cathedrals regained their aesthetic currency and were once again being built. The amazing gothic cathedral of Cologne was the tallest structure in the world from 1880 to 1884. Gardens and parks surged in popularity during the romantic period, as nature made its way back into the cities.

Hiking and mountaineering are romantic inventions from this same period and place, being favorite pastimes of the romantic poets. You can see several romantic elements together at once—the garden, the park, the hiking, the mountains, and the medieval architecture—in the hotels that sprung up in the Alps and other mountain-vacation destinations to accommodate the surge of romance in the hearts of Europeans.3 These hotels, and the expansion of the tourist trade that they represented, owed their profits in large part to the poets who created the utopian romantic vision that they embodied. Among the most famous of romantic poet hikers and mountaineers were Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (Mary Shelley). Their dedication to hiking and mountaineering confirmed a growing sense among the industrializing peoples of their time that nature was beautiful, a source of value and inspiration in its own right. Although we assume without question nowadays that natural beauty is an obvious reality, this was not a common opinion prior to the romantic movement. For thousands of years mountains had been seen as impediments to human habitation and travel, not as things of beauty. The romantic age changed all of that. Suddenly, landscapes and seascapes were being painted and purchased, and scenes of simple country life were being painted for city dwellers who had a newfound, indeed newly invented, nostalgia for the rural.

Obviously, the surge of romanticism in the nineteenth century represented a surge of recognition of the naturally sacred. In this way, romanticism is a reconnecting of Christian Europeans and Americans with pagan sensibilities. The revival of interest in classical Greece and Rome that had begun as early as the Middle Ages, and had grown steadily since then, flourished in the romantic era. Along with a new interest in Arthur, Lancelot, and Robin Hood, we find a strangely anachronistic interest in Zeus, Hera, Mars, and Venus. However, to think of romanticism as mainly, or even solely, as a return to paganism would be a gross simplification, for Christian themes (such as medieval themes) are equally present in romantic literature and thought. Romanticism is, instead, primarily a counterrevolution to the industrial revolution, inspired in large part by a reawakening sense of the naturally sacred. From a pagan point of view, nature is sacred in its own right, whereas from a Christian point of view, nature is sacred as a work of God—but either way, in romanticism nature came into prominence as good, beautiful, and inspiring.

This change in attitude toward nature continues to the present day. The romantic movement officially came to an end somewhere in the late nineteenth century, when it was replaced by “realism.” But unofficially, romanticism was not replaced, but rather integrated into the sensibilities of industrialized city dwellers. Perhaps because they are in closer contact with the natural world, rural people are more realistic about nature than are city dwellers. Rural people see the weeds, ticks, fleas, death, and disease that are the darker side of nature. Contemporary urbanites, however, accept the beauty of nature unquestioningly. In so doing, they embody the romantic values that sprang into life around the year 1800. This romantic fiber running through the contemporary concept of nature gives environmentalism strength and character. As we shall see in more detail, the romantic movement created a fairly complex image of the proper relationship between humankind and nature, and of humankind’s guilt for renouncing that proper relationship and cutting itself off from nature. This guilt is still prominent within environmentalism and goes a long way toward explaining the environmentalist’s rapid and uncritical acceptance of the need to rescue nature from human science and technology.

8.2 ROMANCE AND SCIENCE

The only female mentioned among the list of famous hikers and mountaineers of the romantic era was Mary Godwin, who as Mary Shelley would create a classic romantic figure, Frankenstein. Her “monster,” who in the popular imagination mistakenly bears the name of its scientific creator, is usually thought of as epitomizing the horror genre, which in turn is usually thought of as not only distinct from romance, but its polar opposite. In fact, horror as a literary or artistic genre was also a creation of the romantic age. Byron, who of all the romantic poets had the strongest interest in the gothic and the grave, launched the vampire as an image of horror, while Mary Shelley did the same for the monster of Frankenstein. Her monster crystallizes in a single image the romantic vision of what the scientist makes of humankind. Her monster still states with brilliant clarity what her now-forgotten male counterparts struggled to express in their many volumes of published poetry. It is by no means a mere coincidence that environmentalists today instinctively call genetically modified crops “Frankenfoods.” You can almost picture the genes of these crops stitched together from bits, just like Frankenstein’s “monster.”

It was Mary who understood that for the romantic, scientists are sorcerers. She understood that the romantic line of descent of the post-Newtonian scientists of her times was from Goëthe’s Faust, and before him the medieval alchemists characterized by the legendary Merlin,4 and before them the ancient scientists characterized by the legendary Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods and gave it to humankind. From the outside, the scientist and the sorcerer are indistinguishable to those who are neither. The scientist, like the sorcerer, must study arduously for years under the masters of his art to gain control over the powers of nature. The scientist, like the sorcerer, can leash or unleash the powers of nature by means of acts that seem to have no resemblance or relevance to their results. To the uninitiated, a scientist halting a plague by sticking needles in people’s arms is just as mysterious as a sorcerer halting a thunderstorm by blowing magic dust into the wind.

Modern science is accepted in large part because of the magic it does. It is natural, not supernatural, magic, but magic nevertheless. Fire spurts from a match, electric fire is released from dammed-up water, and a fiery rocket puts a camera in orbit so that we can see the Earth below. Scientists’ control of the elements, particularly fire, is proof of their power. The modern scientists’ release of nuclear fire in an atomic weapon is proof that the magic in their books and formulas is more powerful than the magic in the books and incantations of the sorcerers of common legend. The fact that scientists use formulas, never incantations, is precisely what distinguishes them from sorcerers. Incantations are supernatural instruments. God, the most super of all supernatural beings, created heaven and Earth simply by commanding them to exist. An incantation is a magic command to the powers of nature to do one’s bidding; incantations are intrinsically supernatural. But while the book of the sorcerer shows how the elements can be controlled by means of incantations, the book of the scientist shows how to control the elements through the runic formulas of natural laws.

Thus, modern scientists have intensified and consolidated the powers of the sorcerers of old. They are no longer hostage to the will of supernatural agents who must be propitiated. Instead of making imprecations and incantations, they pull the switches and levers that control the machinery of nature, using the natural power of their own hands and heads. The scientist, Dr. Frankenstein, did not need to call upon higher powers to create his “monster.” In modern movie representations scientists do not call down the thunder of the gods but capture lightning with lightning rods. Scientists take what they need from nature. It is the scientists who tell the story: They set out to perfect human nature, to create a perfect human being, but instead, created the monster out of bits of human beings. The monster grew out of Dr. Frankenstein’s intellect, the intellect that “murders to dissect” but cannot put the pieces back together again. Dr. Frankenstein’s attempt is not only doomed to failure, but makes a creature that is pathetic.

An anatomy text divides the body into its scientific components: bones, muscles, tendons, cartilage, veins, nerves, heart, and brain. The intellect is directing this dissection of the body, just as it directs the dissection of nature in general. The intellect carves up nature precisely where the knife finds the going easiest: at the joints. Scientists say that a good theory is one that cuts nature up at the joints. Knife and intellect are natural allies, hence it is inevitable that “our meddling intellect misshapes the beauteous forms of things.” But where Wordsworth invites us to “close up the barren leaves” of the anatomy text, Mary Shelley boldly shows us the monsters that science will create. Her monster, the first Frankenperson, is a harbinger of Frankenfood (genetically modified crops) and Frankensheep (the first genetically engineered animal)—and all the Frankenpeople that environmentalism warns us we will become in the brave new world of science and technology.

8.3 ROMANCE AND ALIENATION

Romanticism gives expression to the emotional tensions that arise from modern man’s alienation from nature. The romantic sees that industrialized life separates us from nature and infers that in doing so, civilization cuts us off from our own nature. This is a plausible hypothesis today, even though our concept of the genesis of human nature is different from that of the romantics of the early nineteenth century. Darwin ironically proved the romantic’s idea that human nature is rooted in nature at large, and by implication that Homo sapiens has moved beyond its roots. Human nature was shaped by evolution to survive in a world very different from the world we have made for ourselves and now inhabit. We have the instincts that evolution provided us, instincts that were adapted to the life of the hunter-gatherer. Agriculture and city life (the two always go together) have provided us with more food than hunting and gathering ever could, but it has also pent up our hunter-gatherer instincts. We are free neither to fight our urban adversaries nor to flee from them. Our lusts may not go where they list.

City life suppresses our drives for fighting, fleeing, and sex in exchange for satisfying our drives for feeding and families. Food and shelter have always been the main promises of city life, and it has now delivered both in sufficiency and even excess. Whereas starvation was the specter raised by Malthus, it is actually obesity that threatens us now. Scientists describe a global epidemic of obesity. Evolution has taught us to eat whenever we get the chance. Our ancestors necessarily include those who were plump enough to survive the periodic famines of preindustrial life, and their hungry genes are inside us now, telling us to eat. The genes inside us sing out of tune with the world outside: This is alienation of a sort many know intimately.

The Garden of Eden is a complex and powerful image that also says that our natural place is in a natural setting, not in the city. However, in this image, shared by a number of religions, both nature and human nature are romanticized. In the Garden we, like Earth’s other animals, had no need to reap or to sew. We neither hunted nor were hunted. There was no disease. In short, we had nothing to fear. We did not even need to fear stepping on thorns or bashing our foot on a rock. We were barefoot like the other animals, indeed totally naked just like them, immune to biting insects and inclement weather. Sex is not mentioned, though presumably Adam and Eve obeyed God’s command to multiply. Assuming they enjoyed sexual union, Adam and Eve felt not even the slightest trace of shame—quite unlike alienated city dwellers, who are ashamed merely to be outdoors naked.

But in the Garden we had nothing to fear and nothing to hide. This defines freedom in its most romantic form: the harmony of one’s inner nature with one’s environment. Romantic freedom has nothing to do with freedom of the will, the metaphysically mysterious ability to act without being caused to act. Romantic freedom is freedom from compulsion, freedom from ever feeling forced to do anything, and especially freedom from ever forcing oneself to do anything. Freedom is never having to exercise self-control, of always doing what one is inclined to do, like the wind that bloweth where it listeth. We have lost our freedom, according to story of the Garden, because of our sin of disobedience to God, which in turn grew out of our arrogance and pride. God punished us by making nature our opponent, our antagonist. From now on, nature would not willingly give us the necessities of life, and so we must plow and plant and herd and harvest to force the Earth to yield us a living. Eating, a perfectly natural process in itself, has been turned from a pleasure into a chore. Giving birth—also a natural process if ever there was one—becomes painful. The romantic concept of our alienation from nature corresponds quite closely to the curse placed upon us as we were expelled from the Garden of Eden: From now on we would find nature to be our opponent rather than our friend. The first casualty of this alienation is our freedom from death, suffering, and work.

To some extent the science confirms the romantic image. We have to get up in the morning and have to work. Work, by definition, is activity that we do not like to do. The birds of the field, by contrast, never have to do anything that they do not like to do. They never have to force themselves to do anything. They don’t wake themselves up with an annoying alarm clock and drag themselves off to look for food. Instead, they wake up when they feel like it, and when they feel hungry, off they go and eat. The birds of the field do not experience compulsion from without or within, so they have a sort of freedom that we can scarcely imagine. But if we consider animals more like us, science disconfirms the romantic image. Chimpanzees, our nearest genetic neighbors, are highly social animals who must therefore confront a wide variety of social forces that constrain and mold their instinctive behavior. From an early age, their eating, playing, fighting, wandering, sexual behavior, sleeping, and waking are controlled by their elders and shaped to meet the needs of the group. So, long before agriculture or civilization, our ancestors already felt the pressure to conform. Freedom was compromised long ago in our evolutionary ancestry. Alienation from one’s own instinctive nature runs deep in our branch of the evolutionary tree.

8.4 THE CLASSICAL ROOTS OF ROMANTICISM

Shelley based Frankenstein on the classical Prometheus. She learned of the Prometheus myth from Byron, who was fond of Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound. In Aeschylus’s treatment of the myth, there is no action, only Prometheus chained to a rock where he is being tortured for giving us the fire he stole from the gods. He stole the fire so that we would have the power to resist the gods themselves, and the gods are punishing him by having his liver eaten each day by an eagle (his liver is magically restored, so Prometheus can be tortured again the next day, in a foreshadowing of the Christian image of eternal damnation). From his eternal deathbed Prometheus speaks his eternally truthful confession to us, his human audience. Prometheus apologizes to us eloquently for angering the gods, reminding us that he brought us out of the caves we had formerly inhabited—assuming an image of human origins that we now take to be scientifically correct. Aeschylus knew that his audience knew the myth of Prometheus before they ever sat down to watch his play. They knew that the reason that Prometheus stole fire in the first place was to prevent Zeus from exterminating the human race. They also knew that this resulted in both good and evil. The good was that we escaped God’s plan for our extinction, and the evil was that the gods stopped looking after us.

The romantic sense that there was a golden age in the past when human life and humankind was far happier and nobler was expressed in the Promethean legend. In that legend, the gods used to look after us like parents look after their children, tending our every need and nursing our every wound. We had been thrown out of the parental nest because Prometheus had stolen fire and given it to us. In Aeschylus’s retelling of this story, Prometheus seizes the chance to explain to us that he is not our enemy. He reminds us that caves are dank, dark, and dirty. He reminds us that the gifts he gave us are agriculture, architecture, writing, metallurgy, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine—a list that recapitulates the historical trajectory of the human species from its hunter-gatherer past into the cities his audience now inhabits. He reminds us that we are warmer, dryer, better fed, and healthier than when we were in the caves. He reminds us that we have come out of the darkness and into the light spiritually as well as physically, that we can now understand how the heavens go and can interpret our dreams.

Whether or not Aeschylus’s human audience accepts this apology, it knows in its bones that it is not related to nature in the same way that other animals are. According to some strands of the Prometheus myth, Prometheus himself was the creator of the human species, which he had constructed from clay and water, and that his fatherhood of humankind was the reason he bore it such affection. Humans have a different creator than does the rest of natural creation. Aeschylus’s audience knows that it is out of joint with the natural world, that its genesis involved some sort of crime against God, with the result that humankind is an uneasy hybrid of the natural and the divine—exactly what Mary Shelley’s audience also knows. So it is no accident that Shelley sees the scientist as a new Prometheus—the bringer of fire, science, and civilization. It is also no mere coincidence that Mary Shelley’s father, the philosopher William Godwin (1756–1836), taught that human nature is perfectible, since the perfect man is precisely what Frankenstein was trying to create when he, instead, stitches together his monster. Godwin inspired not only his daughter’s creation of Frankenstein, but Malthus’s theory of unending human misery as well. The very idea of the perfection of humankind—or even its improvement—met with instinctive rejection on both romantic and religious grounds. The myths of Prometheus, Frankenstein, and human condemnation express a sense of human guilt and alienation that outweighs any message of hope.

Godwin’s rebuttal, that human population was steady in Western Europe despite increasing food supplies, was mere data that disconfirmed Malthus’s theory but was no match for its mythical resonance. Religion reaffirmed humanity’s sense of unworthiness. Lucifer, one of the names of Satan, means bringer of fire.5 Both Satan and Prometheus lacked respect for their god. One way or another, humankind’s alienation from both the Earth and the heavens is always explained as caused by pride or arrogance or both. The Prometheus legend, and the story of Satan, provide humankind some explanation—and justification—of their need to work, suffer, and die. The only justified suffering is just punishment. The explanation that both Prometheus and Satan provide is that fire was stolen from the gods, and that our continuing use of it is arrogance. They have given us a power that we lack the virtue to possess. Our science and technology, symbolized by fire, alienates us from both nature and God (or the gods). This makes a lot of sense, inasmuch as the things that distinguish us from the rest of nature are also the things that separate us from it. In any case, the sense that humankind is out of joint with the natural world is pervasive and ancient. The romantics knew this, and they knew that the industrial revolution was merely the latest wave in a tide that had been carrying their species progressively farther and farther away from the rest of nature for millennia. They knew that our feeling of alienation was as old as civilization and agriculture, and that every step forward created its own echoes of self-doubt.

Yes: Environmental degradation has been unchecked over the last few decades and is inevitably going to come to a head, with devastating results. Human beings have proven historically that they are psychologically incapable of dealing with crises until too late. Warnings about pollution were ignored for centuries until human beings began literally dropping dead in London streets in the pollution crisis of the 1950s. That crisis was staved off with techno-fixes, new “environmentally friendly” pesticides that do not immediately cause massive death of innocent plants and animals, and “pollution control technology,” which captures only the grossest pollutants from our industrial wastes. Meanwhile, technology has charged ahead like the headstrong adolescent that it is, giving us nuclear power, Frankencrops, Frankenfoods, and a spike in population that is clearly unsustainable, especially if humans in the developing world persist in their doomed attempt to reap the levels of “prosperity” already being squandered by the greed-driven developed world. Now there is a new threat, bigger than all the rest: global warming. True to form, humans have ignored repeatedly the warnings to cut back on their manic use of fossil fuels or have made promises to do so that have proven hollow. Global warming is the keystone crisis, the one that will assemble into a formula for disaster the individual environmental crises that we touched on so briefly above.

No: Dire warnings for humankind have been the norm throughout the ages. If people are psychologically incapable of heeding apocalyptic warnings, as you say, that may be because they have been producing apocalyptic visions which in the end were proven false, one after another, for centuries. Something in the human psyche, perhaps the recollection of the lost security and innocence of childhood coupled with the knowledge of the inevitability of death, makes us project our fears upon the larger world around us. Apocalypse has been the stuff of myth and religious zealots for millennia, but in this scientific age we would be wise to let it go.

Yes: You misunderstand the current state of play completely: It is science, not myth or religion, that is the basis of our current “apocalyptic” warnings.

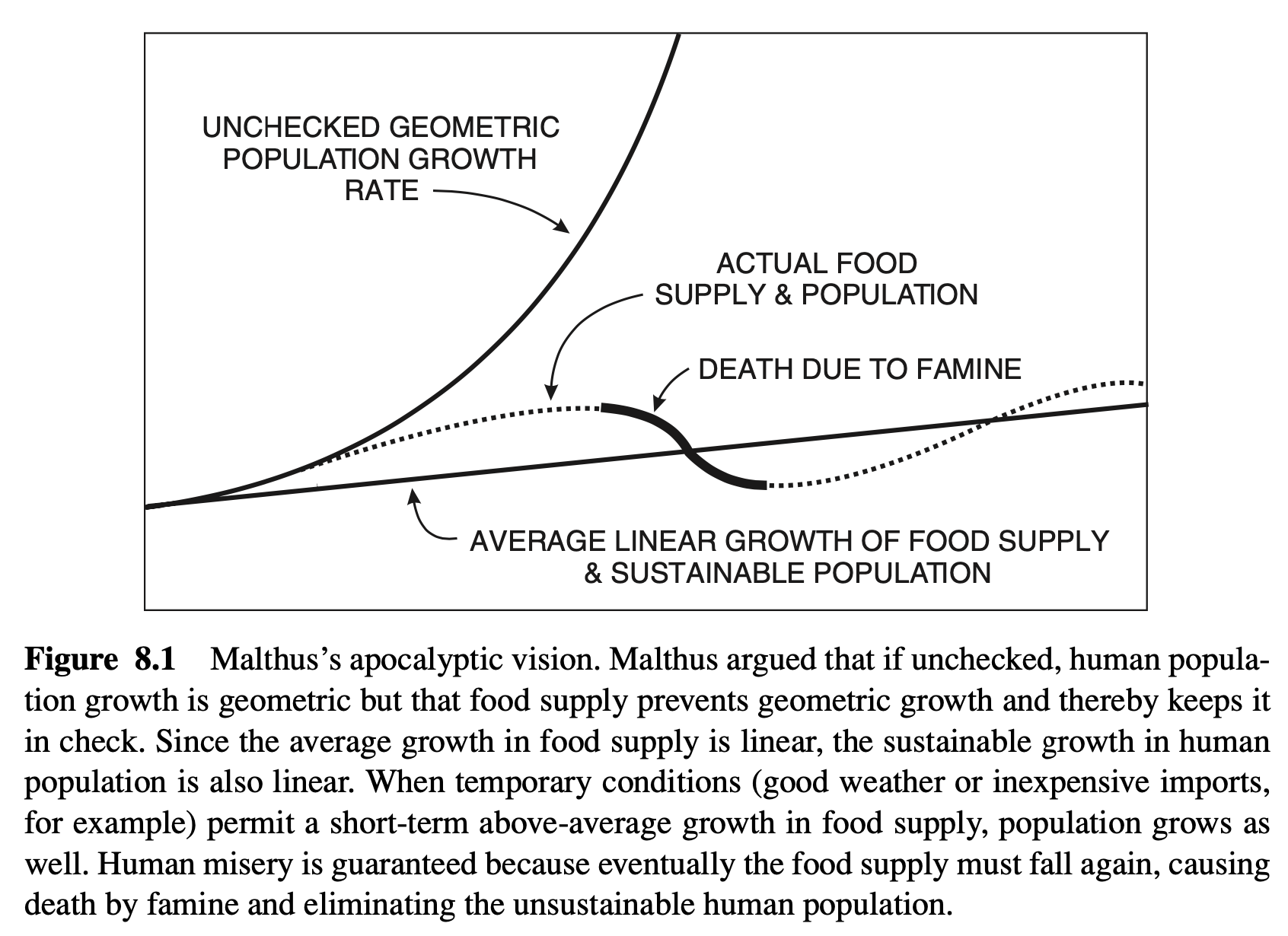

No: Some scientists have, admittedly, gotten into the doom-saying business just like their religious predecessors, but that alone does not make their dark prophecies realistic. As we saw in Chapter 6, scientists are not perfect, and the use of scientific methods does not guarantee that human fears, desires, and other pre-judgments (prejudices) will not also play a role. We need only look at the case of Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), who was both a priest and a scientist, to see that this was so. His scientific model was seen as irrefutable at the time, like the greenhouse model today. His Principle of Population (Malthus 1798) is elegant and easily understood, as illustrated in Figure 8.1: The food supply grows arithmetically (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, . . .)

and so obviously cannot keep up with unchecked population, which grows geometrically (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, . . .). However, population is ultimately kept in check by starvation—assuming that disease, pestilence, and poverty fail to do the job on their own. So population is kept at a sustainable level by, in a word, misery (which, argued Malthus, in turn breeds vice) vindicating the biblical vision of human life as he understood it.

Malthus thought of his scientific theory as an explanation of misery and vice and in effect a proof of Christ’s dictum that we shall always have the poor with us. Like you, chastising the human race was an essential element of his apocalyptic vision. Malthus argued that his model proved that it is pointless to try to increase the food supply to relieve human starvation, because starvation, along with other forms of misery, is inevitable. This was an early argument against what environmentalists call the “techno-fix.” As you can see in Figure 8.1, if for whatever reason the food supply happens to grow faster than the average linear rate, this will cause a spurt in population growth which cannot be sustained in the long run (for, by definition, in the long run the food supply grows only at the average rate). This will, in turn, cause an increase in the death rate, and the good news of the temporary spurt in food supply and population will be followed by deaths due to starvation.

Malthus warned that people must rein themselves in instead and accept their inevitable suffering and limits. His call for self-control and self-sacrifice is a feature common to apocalyptic warnings down through the ages, including the contemporary apocalyptic vision portrayed by the global warming theory. Malthus professed that population should be controlled by “positive checks” such as starvation and disease, and encouraged “preventive checks” such as sexual abstinence. In the same vein, Malthus argued against those who wanted to reduce the misery of the British poor by reducing import barriers to foreign grain (i.e., by repealing the English corn laws), saying that this artificially created spurt in the food supply would only lead to greater misery in the end, just like a natural spurt in the food supply. While Malthus’s view prevailed, people stole bread, with the result that misery bred vice just as he predicted, and when they paid the penalty for it through imprisonment or hanging, this bred yet more misery, again just as he predicted.

Malthus’s model is generally thought to have been disproven: Misery has decreased, despite a constant growth in population, due to such scientific and techno- logical advances as the “green revolution” and birth control. People such as Jeremy Bentham, who argued for repeal of the corn laws, were vindicated. The corn laws were repealed, food did become cheaper in Britain, and starvation was alleviated—without an apocalyptic backlash. Globally, food supply has also accelerated to keep up with the geometric growth of population. Malthus’s mistake, it is generally agreed, was to overlook the inventiveness of human beings.

Yes: We do not yet know that Malthus was wrong. All we know is that the day of reckoning has been postponed—so far. The “inventiveness”—or more properly speaking the craftiness of human beings—and their techno-fixes cannot save them forever from the day of reckoning. That simply does not make any sense, and we can see the gathering storm on the horizon. Obviously, the human population is going to reach a crisis level when it gets to 10 or 15 billion people in this century. It is not possible for Earth to sustain that many people at the levels of material prosperity we have come to expect as our right in the developed world. Obviously, the human economy cannot persist in its policy of endless growth. Only cancers grow without constraint, and they kill their hosts in the process. We, too, are in danger of killing our host, Mother Nature, as global warming proves—unless we change our ways.

No: World population will rise only to 9 billion, and global warming is merely the latest expression of the human need for an apocalyptic vision. Those of us who have been alive long enough remember that back in the 1970s, when lower-than-normal temperatures caused record low winter temperatures, warnings that the next ice age was upon us were very common (Gribbin 1973, Ponte 1976). These warnings were also based on the most sophisticated climate science of the day concerning ice ages, namely the Milankovich theory.7 That theory, which was accepted through the usual scientific consensus, said that an ice age is overdue (see also Ruddiman 2003). Yet instead of an ice age, we got 20 years of rising temperatures. Global warming is also said to be the consensus view of the most sophisticated climate science of the day, but that does not prove the theory to be true. The fact that the global warming theory is tied intrinsically to thundering rebukes of human greed (in this case because they use fossil fuels) actually puts the theory in a worse position than that of the overdue-ice-age theory of the 1970s. The casting of blame is a trademark of the same old doom-saying tendency that has kept prophets in business as far back as our historical records can take us.

Yes: Modern prophets do not rely on reading sheep’s entrails and fear-mongering. To take a prime example, Al Gore has won a Nobel prize, the most prestigious scientific award in the world. As he shows in his movie An Inconvenient Truth (Guggenheim 2006), global warming is already happening, and is based as firmly in scientific fact as tomorrow’s sunrise. He shows us that the seas will rise 30 feet or more, devastating the great coastal cities and other low-lying areas. The Netherlands will disappear. The lowlands of Bangladesh will disappear. Where are the hundreds of millions who live close to sea level going to go? And Gore is not alone in his warning. To cite just a couple of examples, the prestigious journal Science recently published an article (Kerr 2006) which predicted a sea-level rise of 6 m. The prominent science journal Scientific American featured an article with the telling title “Defusing the Global Warming Time Bomb” (Hansen 2004), which warns that global warming will cause “explosively rapid” (p. 74) disintegration of glaciers and sea-level rises of “several meters or more” (p. 68). These scientific warnings are everywhere—all we have to do is open our eyes and face up to what we see.

No: There is no denying that some scientists do make these warnings, but we should not jump to dire conclusions just yet. A closer look at Kerr’s article shows that he merely speculates that there might just conceivably be a 6-m sea-level rise, while actually forecasting a rise of a mere 0.2 m over the next century on the basis of the evidence he presents. That comes to only 2 mm (about one-twelfth of an inch) per year, which is hardly apocalyptic. As for Hansen’s article, we might remember that Scientific American is a popular science magazine that has to sell copies to nonscientists in order to stay in business. Anyway, a close reading of his article also shows that he does not actually predict these events, but instead presents them as within the range of possible effects of global warming. As for Al Gore, he does not predict catastrophic floods either. Instead, in his movie he draws a “what if” portrayal of the worst-case scenario. And by the way, Gore is not a scientist, and he did not win a Nobel prize for science, but for promoting peace.

Yes: The IPCC is a scientific body, a Nobel prize–winning body at that, and it also predicts a catastrophic rise in sea level. This body of internationally acclaimed scientists represents the work of yet thousands of other scientists as well. It is their work that supports people like Gore. He is just their messenger.

No: The actual change in sea level cannot hope to match the rate of change in the IPCC’s own predictions. The IPCC predictions of the coming apocalyptic “flood” started out small—contrary to their own media releases and their exaggerations in the resulting media frenzy—and then shrank again with each new IPCC assessment report. Its first report in 1990 forecast a sea-level rise of only 25 inches (0.64 m) by 2100. Obviously not the Biblical flood, although interesting enough from a scientific point of view. Five years later, in 1995, the forecast fell to 20 inches (0.50 m), then it fell again in 2001 to 19 inches (0.48 m). In the latest IPCC report in 2007, in the face of evidence that it simply could no longer ignore, the forecast plunged to a mere 8 inches (0.2 m). Since the background rate of sea-level rise over the last few centuries is estimated to be 7 inches per century, the effect of global warming itself is tiny: 1 inch by 2100. Given that we have been easily accommodating a rise that is seven times that for centuries without anyone even noticing any problems, the additional inch will not be noticed either. This is not the apocalypse! And by the way, the Nobel prize awarded to the IPCC was also for peace, not for science (in fact, it is half of the prize given to Gore, which they shared).

Scientists are not immune to hysteria, but the scientific community cannot be blamed for the current hysteria about rising seas. The media is in the business of selling newspapers, magazines, television programming, and advertising for all of the above, so they have capitalized on the most newsworthy: that is, the worst, scenarios science can give them. But the scientific facts do not support their apocalyptic vision. When it comes to melting ice caps, the bulk of the arctic ice cap floats on the sea, and when floating ice melts, it decreases in volume to occupy precisely the same space as before, thus causing no rise in sea level.8 As for glaciers on land, basic science tells us that even in the worst-case scenario of global warming, the bodies of ice on Greenland and Antarctica would require many centuries to melt (Bentley 1997), if they melted at all. Anyway, many of the IPCC’s own climate models predict a buildup of glaciers, especially in Antarctica, as evaporation, and hence precipitation, increases. The small sea-level rise predicted by the IPCC is not predicated on melting glaciers in the first place, but on the thermal expansion of ocean waters as they warm up—assuming they do (and apparently they are not).9 Some scientists calculate that the loss of ocean water to the growth of glaciers will counterbalance the thermal expansion and yield no appreciable change in sea level (e.g., Bugnion 1999). Finally, as far as actual measurements are concerned, the rate of sea-level rise has remained unchanged since the early twentieth century (Nerem (NASA) 1997, Luick 2000, Luick and Henry 2000).10

Yes: Rising seas are just one threat among dozens or hundreds that now confront us. Even if some of these threats do not come to pass, there are still plenty of others left to cause us grief. For example, there is no doubt that there have been hurricanes of unprecedented power and fury in recent years, and this fulfills the predictions of global warming. The IPCC predicts an increase in hurricanes and hurricane intensity (IPCC 2001b, Sec. 9.5; 2007a, p. 74). If you trust the IPCC when they predict a moderate rise in sea level, then to be consistent you must trust them when they predict catastrophic storms.

No: Just because someone is right about one thing does not mean that they are right about everything. Anyway, the point being argued is not that the IPCC is right, but merely that it does not predict the apocalyptic flood that Al Gore pictures in his movie. In any case, we have to look to the evidence when it comes to prophecy of any sort, and simple observation shows that both the number and intensity of hurricanes has decreased slightly over the last century (Landsea et al. 1996, E. Smith, 1999).11 And we might do well to remember that in 2005, Landsea resigned from the IPCC over what he called its continual misrepresentations of this issue in the global media (see Section 2.1).

Yes: When it comes to the evidence, there is no denying the warming in the Arctic, and no denying it is the harbinger of global warming. Arctic sea ice is thinning at an alarming rate. Polar bears are dying because they have no ice floes on which to hunt. Arctic sea ice has broken up during recent summers, and the Northwest Passage has opened up for the first time in recorded history.

No: Arctic ice often breaks up in the summer: It is, after all, floating on a large, windy, and moving sea that is warmed by the Sun 24 hours per day during the summer.12 In addition, the prophecies of the collapse of the Arctic ice sheet have been withdrawn. The latest IPCC report (2007a) has abandoned the claim of catastrophic Arctic warming, and now says merely that “Arctic temperatures are highly variable.” In fact, it even admits that a “. . . slightly longer warm period, almost twice as long as the present, was observed from 1925 to 1945 . . .” (AR4, p. 37). (We might suspect, by the way, that describing a warm period that is almost twice as long as only “slightly longer” indicates that there may be some rhetoric involved in the IPCC assessment reports.)

Yes: The breakup of the Ross ice shelf and other enormous bodies of ice in Antarctica shows that something unprecedented is going on with the climate: It is warming up, just as global warming predicts. We seem to have reached some sort of tipping point for global climate.

No: The Ross ice shelf, like all ice shelves, is formed by glacial ice flowing out over the open ocean. Since these shelves can extend for 100 miles or so and are only hundreds of yards thick, their width is thousands of times greater than their thickness. They are called shelves, but if so, they are extraordinarily thin, like a shelf made of paper. Ice shelves must, and do, break up periodically, as they get too large to be structurally stable. Anyway, the ice shelves are just a tiny bit of the Antarctic ice. Satellites show that the total amount of Antarctic sea ice, including the Ross Sea, continues to grow year by year (Parkinson 2002).13

Yes: The very credible World Health Organization (WHO 2003) warns that heat waves will kill thousands. We have already seen this begin to happen in Europe in recent years. This is completely analogous with the deadly London fogs of the 1960s. Surely you cannot ignore the deaths of your fellow human beings.

No: Heat waves used to kill even larger numbers before the introduction of air conditioning, and death rates fall below normal immediately after heat waves, revealing that they only hasten the deaths of those already mortally ill and too poor to afford air conditioning (White and Hertz-Picciotto 1985, pp. 184–189). In addition, we know that cold weather causes more deaths than warm weather, and that warming would therefore decrease the total number of fatalities (White and Hertz-Picciotto 1985, p. 184; McMichael and Beers 1994). So even if global warming happens (and in this context we should perhaps consider the various sorts of evidence for and against marshaled in Case Study 7), it may do more good than harm as far as death due to extremes of temperature is concerned. According to the proponents of global warming themselves, maximum temperatures will not rise significantly anyway. The bulk of the predicted rise in temperature is supposed to occur in minimum nighttime lows and winter averages. In short, global warming theory predicts that extremes of temperature will decrease, not increase. Since health problems occur in temperature extremes and rapid temperature changes, the overall effect on human health would be positive.

Yes: But global warming will bring a modern-day plague of tropical diseases into Europe and North America (IPCC 2001b, Sec. 9.7.1). The species of mosquito that carry malaria are now restricted to the tropics, but once the climate changes they will be able to move north. Surely a malarial plague counts as apocalyptic even for skeptics.

No: There is no evidence of this happening. In fact, there is evidence indicating that there is no link between malaria and such small temperature changes (Hay et al. 2002). Disease is linked far more tightly to poverty than to weather (Taubes 1997, Hay et al. 2002), so if we want to prevent a modern apocalyptic plague, the best thing we can do is to make sure the economy is not harmed by programs such as the Kyoto initiatives, which are supposed to (merely) slow down global warming by stopping our use of fossil fuels. Sometimes we might do better to remember history rather than to make forecasts, whether scientific or otherwise. It is a common, garden-variety historical fact that malaria was widespread in the temperate zones of Europe, America, and Asia all through recorded history up to the mid-twentieth century. Temperate-zone malaria gradually disappeared in the late nineteenth century, although we do not know why. We do know, however, that the most dramatic increase in malaria in recent history was due to the interruption of mosquito control programs over environmental concerns about DDT some 25 years ago (as we saw in Case Study 4).

Yes: When you isolate the individual signs of the coming apocalypse, doubt can be cast on each. Doubt is easy to come by. However, when they are taken together, they comprise a very credible threat. Even if each threat has a small probability, the probability that at least one of these threats will be realized is very high. In any case, the question we are considering is not whether the environmental apocalypse has been proven, but whether or not the danger of environmental apocalypse is real. Danger does not have to be proven to be real. And danger demands that we do not become complacent.

No: Agreed.

8.5 LOGICAL ANALYSIS OF ROMANTICISM

Romanticism is too complex to be captured fully in a simple analysis, but a rough outline of its main features is both possible and desirable. The heart of romanticism is a sense of lost innocence—a longing for the peace, security, and loveliness of an idealized childhood. Guilt is implied by lost innocence, so we conceive of various sins that we have committed. We have taken, or at least have accepted, something stolen from the gods; or we have disobeyed God. There were two paths, and we took the wrong one. One path, the path of innocence, is one of humility, faith, patience, and submission. The other path, the path of knowledge, is just the opposite, a path of confidence, knowledge, impatience, and defiance. Since we have taken the wrong path, the path of knowledge, repentance is required: We must go back, return to our state of original innocence.

In our hypothesized state of primordial innocence, we were magically free of care, want, fear, strife, suffering, or work. We lost this ideal state through using our knowledge to assert our own desires and to relieve our own fears. In other words, we used know-how, craft, and technology defiantly to take what we were impatient to get: food, clothing, shelter, art, science, entertainment, and so on. So we can regain our innocence only by rejecting technology, rejecting both the physical fires that enable our technology and the psychological fires of impatience and defiance that motivated us to employ technology in the first place. Romanticism asks us to go back, to reverse the entire evolutionary trend of Homo sapiens, to repeal not just the industrial revolution but also, civilization, agriculture, science, and technology. The first mistake, from the romantic point of view, was the use of fire by our distant forebears. We must get off the path of knowledge and get back on the path of innocence.

8.6 THE BALANCE OF NATURE IS A ROMANTIC FANTASY

The most common conceptualization of our environmental guilt is that we have upset the “balance of nature.” Indeed, it was quite common to hear environmental scientists use the concept a generation or two ago, even though it was already known by then that a “balance” did not exist. From a scientific point of view, there is no such thing as the balance of nature. Nevertheless, the concept has such mythical resonance that many of you reading this will be jumping to its defense, (some scientists included, if only in a qualified sense). Certainly, the notion is so useful to environmentalists rhetorically that they are loath to give it up. The idea carries with it the idea of justice, which is also symbolized by a balance. Children reduced to tears by seeing a coyote kill and devour a rabbit can be soothed by the notion that the victim’s suffering and death are all part of the balance of nature: In the larger scheme of nature, its suffering is all for the good, and so is just. By the same logic, the charge of upsetting nature’s balance instantly carries with it the charge of injustice, of upsetting nature’s scheme.

The balance of nature thesis (BNT) is that if left alone—that is, if not affected by human beings—natural systems (ecosystems, etc.) find the ideal balance between predator and prey populations, between wetlands and dry, between warmth and cold, and so on. One implication of BNT is that, among all of the elements of the natural world, the human beings, and only human beings, upset this balance. This is a dubious aspect of BNT, inasmuch as it is an expression of antihuman bias. Since the balance of nature is good, it follows that human beings will be bad, since every effect of human beings upon natural systems will by definition upset the supposed balance. Aspects of global warming theory (GWT), for example, show this antihuman bias, since human effects on climate are immediately characterized as “perturbations”—or disturbances—of natural climate. Thus GWT implies that whatever the climate does or would do independent of human influence is what it ought to do.

There simply is no reason to accept this value judgment. It is merely a romantic expression of antihuman bias on the one hand and of the innocence of nature on the other. We know that the ice ages drastically reduced the quantity, range, diversity, and security of life on Earth. Thus, in terms of environmentalist values, they were bad, not good. The ice ages were also bad in terms of romanticism and its values. Indeed, over the span of millions of years, the history of life on Earth has totally falsified any notion of a time of primordial innocence. From the beginning, life itself has involved external competition between living things with the elements themselves, and internal competition between living things and other living things. We know that the natural world is not like the balance arm of a set of scales, which tends to return to equilibrium if disturbed. It is, instead, like a ball rolling down an endless bumpy hillside (a multidimensional energy surface, to be a bit more precise), bouncing headlong into adventures, and never returning to quite the same state twice. The Earth and its living cargo comprise what physicists call a disequilibrium system, a dissipative system “pumped” by radiation from its local star, our sun. The resulting “system,” like any very complex dynamical system, is most unsystematic. In fact, it is chaotic (i.e., deterministic, but unpredictable) and will periodically generate massive and abrupt (global and discontinuous) change. We know this, or at least the scientific facts are established beyond any reasonable doubt, but we have not come to terms with this reality.

The knowledge that nature is chaotic is like our knowledge of our own death. We all know that we are going to die—and we do not realize the fact. Wisely, perhaps, we put it out of our minds. So when the time comes for us to die and the doctor tells us that we have only a small time left, we are shocked and saddened. Tears come to our eyes and to the eyes of those who love us. Now we are beginning not merely to know that we are going to die, but to realize it, to truly comprehend it, both factually and emotively. In a parallel way, and for parallel reasons, we have been slow to realize that nature is chaotic. For one thing, that would entail admitting that the forms of life we now see are not eternal. Just as each living thing must die, so, too, one day, must all species die, and all the “ecosystems” that we have come to know and love must vanish along with them. Just as the species of old, like the multifarious dinosaurs, are no more, one day there will be no mammals, no coyotes, no rabbits, no Homo sapiens. Wisely, perhaps, we do not dwell on this fact. But whether we dwell on it or not, it is surely unwise to cling to, to believe in, its opposite, the notion of the balance of nature. If we need not dwell on unpleasant truths, we need not deny them either. The return to innocence cannot be purchased so cheaply as by a simple denial of knowledge.

In the biology texts of a few generations ago, the balance of nature was standard fare. Even though it was well known that there had been a recent series of ice ages, and that before this, eras in which none of the current life forms existed, it was nevertheless believed that somehow or other nature struck a balance. For example, it was thought that prey and predator populations were kept in balance. Inasmuch as virtually all animal species play one or both roles (herbivores prey on plants and are in turn preyed upon by carnivores, etc.), this amounted to a massive balancing act. But it could be seen as consistent with casual observation, and the natural tendency to romanticize nature did the rest. Thus, the balance of nature gained the status of an unstated presupposition that was effectively unfalsifiable. Any apparent imbalance could be explained as a temporary disturbance, or perturbation. A series of warm, wet summers might lead to a lot of grass, which then leads to a lot of antelope, and thus a spike in the population of lions—followed by a massive die-off of all three when conditions return to normal. So biological thinking evolved to include the idea that the balance of nature is sometimes perturbed but then returns to the norm, like a balance arm of a scale moved temporarily away from its point of equilibrium.

However, this craftier version of the balance of nature hypothesis conflicted with more careful observation, which revealed that predator and prey populations continued to oscillate even in the absence of known perturbations. So the notion of a natural balance was abandoned in favor of the idea of natural cycles in animal populations. Unchecked impala populations, for instance, would tend to grow, which in turn would cause a growth in the population of lions. The increase would then cause impala numbers to decrease, which in turn would cause a decline in the number of lions, bringing us back to where we started and setting the stage for another cycle. Hudson Bay records of fur trapping were broadly consistent with this cycling model in the case of snowshoe hares and lynxes.

On the basis of this data set and some others like it, the model of natural cycles of population was generally adopted. The model can be elaborated to include potentially all species, whether plants or animals. The lion–impala model, for instance, can be enriched by the addition of a species of grass upon which the antelope feeds, providing a sort of Malthusian check on both the lion and antelope populations. This gives a three-layered predator-prey model, with lions at the apex, impala in the middle, and the grass species at the bottom. Assuming that a model could be devised which actually tracked these three populations, other species could be added, such as cheetahs and leopards at the top, wildebeest and giraffes in the middle, and other herbaceous species at the bottom, without limit, in principle. In principle this model can also be enriched to include biological relationships other than that of predator and prey, such as populations of insects that feed on animal dung, flowering plants pollinated by those insects, and so on. Now the model is not one of a balance arm, but of a series of interlocked cycles linking the populations of all the species, like an enormous set of gears meshing with each other in a massively complex clock.

This model, the standard of professional biologists a generation or so ago and still presented in introductory textbooks, was also discovered to be simplistic and disconfirmed by the data. What the data showed was that cycles in animal populations are inherently unstable. A simple two-layer predator-prey experimental model of microbes in a test tube will sustain only a few cycles before it collapses, often with the death of both species as the predators become so numerous as to exterminate their prey, thereby sealing their own doom. Sometimes larger systems are more stable, sometimes not, at least in the sense that they do not collapse with the death of the organisms involved. Presumably the global totality of life on Earth is stable in this sense. In any case, all of these systems, whether large or small, are chaotic.

So there is no such thing as the balance of nature, but that means that the environmentalist conception of environmental health is based on a nonentity. Environmentalists and their organizations consider the ideal to be the state of nature when not influenced by human beings. Thus, to take a telling example, they believe that human beings should reduce—or eliminate—their ecological footprint. This is sheer romanticizing, an obvious call for us to return to the path of innocence and leave behind the path of knowledge. It is based on belief in human guilt for having upset the balance of nature. However, no argument has ever shown that untouched nature is ideal. Indeed, as the ice ages prove, no such argument can be given. It is merely presumed that human influence always disturbs the natural world. However, to influence nature is simply to change its course in some way, large or small. But change is not bad in and of itself. Yes, some of the changes we have brought about are bad, such as the extinction of some species of plants and animals. But it is simply false that any change that humans bring about is necessarily bad (intrinsically bad, bad as such, bad per se), even if we bring it about through agriculture or industry.

The history of our misty blue–green planet is one of constant unpredictable change. There is no guarantee that had we not devised agriculture, cut down the forests, hunted animals for food, driven cars, and so on, through the usual catalogue of our environmental sins, the natural world would now be in a better state—or even be more to the liking of environmentalists.14 For one thing, given that we have followed the path of knowledge, we have achieved a level of understanding that permits us to consider and care for the health of the living things on this planet, something that otherwise would have been impossible.

8.7 THE ECOSYSTEM IS A ROMANTIC FANTASY

The concept of an ecosystem, or the ecosystem, is a logical cousin of the balance of nature and is used by environmentalists, including applied environmental scientists, for precisely the same purposes: to chastise human beings for their effects on nature, which then will count as “disturbances” or “perturbations” by definition. At a park not far from my house there is a sign saying that the park contains a fragile ecosystem, and exhorting those in the park not to disturb it, to stay on the paths, not to pick the flowers, and so on. The words fragile, delicate, or threatened almost always go just before the word ecosystem. This portrays the natural life of the park as a complex piece of machinery, and at the same time warns us not to be poking our fingers into it. Just as often, we are told that the ecosystem is precious or invaluable. Could it be that every ecosystem is fragile? Life itself, as we saw earlier, is anything but fragile. It is powerfully tenacious. Yet we always find ecosystems described as though they were playing-card towers, ready to collapse at the slightest touch. Human beings are by definition a disturbing influence on these systems, and so by definition are clumsy, insensitive, greedy, and arrogant.

Admittedly, ecosystems are sensitive—that is precisely what is meant by saying that they are chaotic: Everything that happens to them or within them will have effects, some of which may be quite unexpected. But sensitivity is a completely different thing from fragility. Like all living things, a rhinoceros is sensitive, but it is certainly not fragile. The rhino is so sensitive that you cannot sneak up on one without being detected. Similarly, the life in the park of which I speak is sensitive: It responds to everything that happens to it. The main thing that has happened to it in recent years is that it has been identified and protected by humans as being a “fragile ecosystem.” It shows many effects as a result, thereby proving its sensitivity. For one thing, there are many ducks, geese, red-winged blackbirds, and other birds nesting comfortably near the shoreline, raising their families. Were it not for the presence of humans there would be far fewer of these birds, because predators such as coyotes, lynxes, weasels, and raccoons would have gobbled some of them up and driven many of the others away. Clearly, this ecosystem is sensitive and so has responded to the presence of humans—albeit in a positive way as far as nesting birds are concerned.

Actually, it is very misleading here to speak of the ecosystem as sensitive. It is really the birds that are sensitive: They can tell that this bit of shoreline is predator-free. It is predator-free precisely because this bit of Earth’s surface is frequented by humans, which scares away the predators. From the point of view of those who tend to think of human beings as unnatural, the ecosystem of these birds has been upset, affected, harmed by the presence of the humans that wander about on the pathways every day. But it hardly follows from this that the ecosystem is worse for the experience. What is wrong with ducks, geese, and blackbirds finding one more safe place to reproduce? Naturalists break into rhapsodies when natural conditions provide protection from predators, as sometimes happens on islands, allowing prey species to flourish. How, then, can this be wrong when human beings provide—however unwittingly—the same protection? It is wrong only if it is assumed that every effect of human beings on nature is automatically bad. Of course, since this stretch of shoreline is an ecosystem, any human-induced change will be readily characterized as a disturbance.

The idea that a piece of Earth’s surface defined by municipal property boundaries and the organisms on it automatically forms an “ecosystem” is surely more poetry than science. Environmental scientists who employ the concept of the ecosystem can draw an analogy with the physicists’ practice of treating any isolated set of elements as a system. A good example is the solar system. For all practical purposes, the solar system is isolated from the effects of the bodies around it, which permits it to be treated in isolation from the rest of the universe. The Earth and Moon can also be treated as a system, and so can a pendulum or a pot of water boiling on a stove. But arbitrarily chosen bits of Earth’s surface will almost never be isolated in this way. In the case of the park in question, most of its elements are not only affected by things from outside the park but are only passing through it in the first place. The air, the ocean waters, the rain, and the birds themselves come and go in their migratory wanderings, as do the seals, herring, deer, insects, and so on. So it is not a system in the sense used in physics.

Anyway, environmentalists would not want us to think of an ecosystem as just any arbitrary isolated physical system. They want us to think of an ecosystem as a system in the biological sense, not the physical sense. In biology, the paradigm cases of systems are the digestive system, the circulatory system, the nervous system, and so on. These are systems in a very strong sense: They have functions. A function is a process that achieves a goal. The function of the digestive system, for example, is to transform foods into a form that can be put into the bloodstream and then to put them into the bloodstream in that form. Those very words also describe the goal of the digestive system. It can only achieve its goal by virtue of its organized structure, in which hundreds of components cooperate. But an arbitrarily chosen bit of the natural world will not have a function in this sense. A bit of shoreline plus its inhabitants do not make up an organized set of components that achieve a specific goal. All of the inhabitants do have goals, for they are organisms. But although each organisms has goals, it does not follow that the group of them share some higher goal, purpose, or function. A postman’s function is to deliver the mail and the function of the key in his pocket is to open his car door, but he and his key do not form a system with the function of delivering the mail and opening his car door.

To think that an arbitrary subsection of the natural world forms a system is just like thinking that an arbitrarily chosen subsection of a body or a machine would be a system. But an arbitrarily chosen chunk of a body will contain bits of many systems, a bit of the circulatory system, a bit of the nervous system, a bit of the limbic system, and so on. But these bits of systems are not themselves a system. Real systems are composed of a set of parts that cooperate to achieve a goal. But an ecosystem contains a set of contestants that compete for the same goals: food, shelter, survival, and reproduction. Certainly, there are striking instances of symbiosis among organisms, and that is a form of cooperation. The paradigm of symbiosis is that plants breathe in carbon dioxide and breathe out oxygen, whereas animals do the reverse, thus completing a cycle. Given this cycle, it makes sense to speak of the corresponding functions and purposes. But for every example of cooperation there is just as good an example of competition. The animals also eat the plants, and predators eat their prey. Bacteria prey on both animals and plants, and viruses prey on all three. You will not find one set of cells within the nervous system preying on another set.

When it comes to the ecosystem, the total of all of the local ecosystems (however demarcated) taken together, the situation is, logically speaking, even worse. To put it very bluntly, to suppose that there is a function for the entire planet is to accept the Gaia hypothesis. What is the function of the entire planet? Surely it cannot be to maintain conditions so that they are optimal for life. Are we to think that all of the enormous numbers of different conditions that Earth has sustained over the eons were all, every one of them, optimal for life? That would be a lucky coincidence, to say the least. Are we to suppose that ice ages are optimal for life when the total biological activity on the planet is drastically reduced? And if we do suppose that prior to our arrival on the scene the ecosystem was optimal, this has the consequence that the specific set of species that existed at any given instant was optimal. In addition to being improbable simply on logical grounds, alone, this seems incredible on biological grounds. It seems quite likely that the removal of some species would increase the overall life of the planet. Removal of anthrax, for instance, might increase the health of life on the planet.

If in situations like this we are inclined immediately to suppose that even a known pathogen with no obvious purpose must serve some purpose, even if we do not yet know what it is, then we are obviously under the false impression that the planet as a whole is optimal in some way, that it serves some purpose with perfect fidelity. How could we know this when the function of the planet is unknown and the functions of its parts are unknown? Anyway, if we are to suppose that each organism and species performs a function that in mutual cooperation performs an overall function of life itself, how did it happen that we alone among the species are not optimal? If, in the face of these problems, we are inclined to defend the idea that everything has a natural function and that nature itself has one, too, and that we are guilty of upsetting this natural system, we have left the scientific attitude behind and are engaged in romantic fantasy. If, on the other hand, we respect the scientific demand for clarity and observation, we will not assume that the planet is a system in the biological sense. The very idea of the ecosystem is confused. There simply is no such thing.

8.8 OUR SENSE OF ALIENATION FROM NATURE

As we have seen, romanticism begins with our sense of alienation from the natural world, our sense of lost innocence. This amounts to a form of guilt. Do we have anything to be guilty about? Is our sense of alienation justified, or is it also a romantic fantasy? Most of us grew up with pavement under our feet, industrially produced food in our stomachs, and vaccines in our blood. It is a fact that we are separated from the rest of nature, whether or not we are alienated from it. We place layers of technology between us and nature: clothing, houses, umbrellas, automobiles, and so on. We ingest medicines and vaccines to keep nature at bay even inside our bodies. Does this separation entail alienation and guilt?

We are not alone in separating ourselves from the rest of nature. All organisms do it, since life requires distinguishing self from other. In fact, we are not nearly as separated from the outside world as some other species are. Many species of termites, for example, seal themselves up inside the wood in which they live, thus combining food, clothing, and shelter in a triumph of efficiency and simplicity. Some termites build towers, which are termite cities, complete with nurseries and gardens and transportation routes and ventilation channels and termites specializing in the various trades required to tend to them. Termite cities are built, as are ours, to keep the natural world at bay, to deflect the elements and defeat the predators. So, separating ourselves from nature-at-large is not unique to Homo sapiens. But despite this similarity between us and other animals, our separation from nature is more profound than theirs. Like other animals, we have eyes and ears and mouths and noses. We are born, draw our first breath, and eventually our last, as they do. But the works of humankind stick out from the rest of the natural world like red sticks out on green. An automobile and a hamburger are not very similar as physical objects go, but they are identical in one way: They are completely unlike anything else in the natural world. We are far more adaptable than other organisms. Our constructions and our behaviors change continually, and continually become more effective.

But this still does not explain our sense of alienation from nature. Alienation is much, much more than the simple fact of separation. Alienation involves a sense of guilt, a sense of having willfully destroyed a friendship, perhaps for personal gain. Our sense of guilt is easily explained. Our sewers flushing our bodily wastes into our rivers, our factories belching smoke, our fields dewy under our pesticides, all these things that the romantic sensibility instantly sees as the very image of our alienation, involve injuring nature, generally for our own gain. Reason does not jump to our defense on this score. The charge that we have damaged nature is not easily dismissed as a romanticized fancy. Reason tells us, furthermore, that damaging nature is the height of folly, for in damaging nature we damage ourselves. Reason tells us that as far as our self-interest is concerned, the waste-removal technology of civilization has obviously lagged behind the food, clothing, and shelter technology. As late as the nineteenth century, cities such as Paris, London, and Rome were dumping untreated human wastes into the Seine, the Thames, and the Tiber, respectively. Not only did this injure other species, but injured us as well. Our sense of injury to nature is justified, for it is proven by our injury to ourselves as part of nature.