Praise be to You, my Lord, through our Sister, Mother Earth, who sustains us and governs us.

—Saint Francis of Assisi

One of the first things you miss in the wilderness is the bathroom. My brother John and I were camped on a glacier below the peak of Mount Hector when in the middle of the night the normally simple and civilized business of urinating loomed as a daunting, hydraulic necessity. I had put off leaving the warmth and safety of my sleeping bag as long as I could, but now I had to go outside into the cold and dark. I knew that many a climber had died because putting on boots and crampons seems too difficult in urgent moments such as these. They had ventured outside with only boot-liners on their feet, forgetting just how steep and slippery a glacier is, forgetting that once they begin to slip there is no stopping, forgetting life itself as they smashed into a rock or crevasse down below. As I extricated myself from my sleeping bag inside the cramped little tent, I reminded myself that confronting my mortality was one reason I was there—and then promised myself not to go outside in just my boot-liners. I stuck my head out, searching for my boots outside on the glacier where I had left them, trying not to wake my brother.

Our sort of mountaineering had nothing to do with the strategically planned, testosterone-fueled “assaults” on summits that fill the pages of alpinist novels and extreme sports magazines. We had instead set out from the highway, now many miles away, with no “plan of attack.” We had taken our time walking through the broad, increasingly steep forests on the flanks of the mountain, stopping often to admire the terrain or ponder the route ahead. We had free-climbed the first set of cliffs, the ramparts that bar most human beings from the alpine meadows above, a special realm closed to all but a few. Our visit was not an assault on a peak, but our pilgrimage to nature and to the universe that gave birth to her. We were not conquering a mountain, but getting to know it. Rituals of purification had to be followed. Everything we took in had to be taken out again. As far as possible, we would leave no traces in this place. Our mood was one of respect. Joyful, boyish, sometimes gleeful respect, to be sure, but respect just the same. If anyone had asked us why we headed into this wilderness for a few days each year, we would have said that we loved hiking, and that the mountains were beautiful. But just what that beauty consisted in, and how we were able to replenish ourselves with it, is not something easily explained.

Weak and sinful creature that I am, I gave up the struggle to stuff my feet into my cold stiff boots, and stumbled out onto the glacier in my boot liners in defiance of the laws of common sense and self-preservation—gripping an ice ax with which, hopefully, to stop myself should I begin to slide down the slope. The wind that had been flapping the tent a few hours before had died. It was dead calm, almost warm. Looking down the slope I saw the top of Mount Andromache, which had towered above our camp the night before. Fighting down my giddiness and fear, I turned round to look upward to the mountain. The glacier shone down on me with a strange light, making it hard to see. My senses were keen, but the silence was deafening. The ice rose up steeply for a few hundred meters, and then crested. Far beyond the crest I could make out the massive stone cairn that was Hector’s peak, a black presence towering against the myriad stars. With a dizzying shock, I realized the mountain itself was moving. The peak was plowing through the stars, eclipsing them in bunches as Earth turned on her axis. Suddenly I saw for myself what before I only dimly realized: Earth is a ship hurtling through space. Here I was in a window seat. As I peered out I saw that I and every other living thing was defying the odds just by being here. I was elated yet humbled, terrified yet reassured. I saw that not just my life, but life itself, was vanishingly small—and infinitely precious.

7.1 NATURE AND RELIGION

It is natural to hear the forests, mountains, or seas called sacred, holy, primeval, primordial, worthy of reverence, and so on. These terms are the same as those used by the religious to describe the godhead. Most people intuitively understand experiences of self-enlightenment and oneness with nature that are evoked by wilderness. Indeed, we know that the oldest forms of religion, the pagan religions that predated modern monotheistic religions, were closely tied to these experiences evoked in natural settings. The very first churches and temples were not buildings but natural sites, such as groves, trees, outcroppings of rocks, bits of shoreline, and so on, that most strongly evoked the natural sense of the sacred. People came to such sites and camped in them long before any buildings were erected in them.

The celebrated ruins of Dephi, the holiest site in ancient Greece, are the remains of only the most recent temples built where people had come for thousands of years to experience natural, sacred beauty. As one ascends to Delphi from the plain below, one passes through “. . . increasingly rugged and remote territory filled with history and myth. Finally, the dramatic scenery of the limestone cliffs, from which gushes the Castalian Spring with its great cleft, comes into view . . .” (Ching et al. 2007, p. 121). Unsurprisingly, given the richness of human thought and social life, the “…early history of Delphi is the story of a struggle between different types of religious practices. Initially, the site was dedicated to the great mother goddess in the Minoan tradition. With the arrival of the Dorians, we see the maternalistic element superseded by the paternalistic world concept of the Dorians” (ibid.). But the transition from one religious conceptualization of a naturally sacred site to another does not mean that the former is completely erased by the latter: “Nonetheless, despite the seizure of the shrine by the followers of Apollo the new religion did not obliterate the old, but metamorphosed it into its own mythologies. The mother goddess was transformed into the serpent Pytho who is said to be buried there” (ibid.). Indeed, the sense of the sacred in nature is extremely deep and in this sense primitive, like a root connecting us to our distant beginnings: “Furthermore, the Earth goddess, Gaia, as she came to be called by the Greeks, retained her ancient temenos [sacred ground] close to the temple of Apollo, near the rock of the Sybil” (ibid.).

In the Japanese Shinto tradition we see the primordial, natural roots of the sacred still feeding a contemporary religious tradition. The holiest Shinto shrine is set in a beautiful forest on “a narrow, verdant coastal plain” that is “relatively warm even in winter” (op. cit., p. 279). In Shinto, “… every aspect of nature was revered. There were no creeds or images of gods, but rather a host of kami. . . . Kami were both deities and the numinous quality perceived in objects of nature, such as trees, rocks, waters, and mountains” (op. cit., p. 278). So, unlike the ancient Europeans, the Japanese did not overlay their sense of the naturally sacred with complex and determinate mythologies. Perhaps because of this, the sites which evoke the sense of the sacred for them still function today as they did in the far distant past: “The kami that are still venerated at more than 100,000 Shinto shrines throughout Japan are considered to be creative and harmonizing forces in nature. Humans were seen not as owners of nature, or above and separate from it, but as integral participants in it and indeed derived from it” (ibid.). An additional benefit of the Japanese tradition is the clear realization that human beings are completely natural, a realization that must be an element of any sound philosophy of nature. Environmentalism, by contrast, is based on the tragically misleading—and false—dichotomy between human beings and their surroundings (environs), that is, their environment.

Aboriginal peoples from around the globe experience the beautiful and the sacred in nature. The indigenous peoples of North America, for example, confirm the pattern of connections we have seen in the primordial cultures of both the Eastern and the Western parts of the old world. “In the songs and legends of different Native American cultures it is apparent that the land and her creatures are perceived as truly beautiful things. There is a sense of great wonder and of something which sparks a deep sensation of joyful celebration” (Booth and Jacobs 1990, p. 520). Once again, we see that the sense of the sacred is evoked by the beauty of nature, and once again we see this sense expressed in ways that recognize that we human beings spring from nature and thus are fully natural: “Black Elk, a Lakota, asked, ‘Is not the sky a father and the earth a mother and are not all living things with feet and wings or roots their children?’1” (op. cit., p. 521). Human naturalness and our connection with all other natural things is experienced as kinship and affection: “Luther Standing Bear . . . describes the elders of the Lakota Sioux as growing so fond of the Earth that they preferred to sit or lie directly upon it.2 In this way, they felt that they approached more closely the great mysteries in life and saw more clearly their kinship with all life” (op. cit., p. 522).

Unfortunately, some other people’s sense of kinship with nature has grown more tenuous. “Standing Bear comments that the reason for the white culture’s alienation from their adopted land is that they are not truly of it; they have no roots to anchor them, for their stay has been too short”3 (ibid.). Whether or not Standing Bear’s explanation is correct, environmentalism aids and abets this sense of alienation by using it as its foundation. Correcting this subversion of our sense of the naturally sacred is the first task of any adequate philosophy of nature.

7.2 CHRISTIANITY AND THE “ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS”

Standing Bear’s comment brings us to a topic about which there has been enormous discussion and publication: the sense that modern industrialized peoples have lost their sense of connection to nature and the sacredness of nature. This loss has been blamed for the so-called “environmental crisis,” and countless essays and books have been written lamenting the loss and advising—or exhorting—industrialized peoples to regain what they have lost by learning from their preindustrialized brothers and sisters. In a famous essay, published, in of all places, the prestigious scientific journal Science (about which more anon), a historian of science, Lynn White (1967), laid the blame for the environmental crisis squarely upon Christianity. No words more efficiently express his charge than his own: “. . . viewed historically, natural science is an extrapolation of natural theology, and . . . modern technology is at least partly to be explained as an Occidental, voluntarist realization of the Christian dogma of man’s transcendence of, and rightful mastery over, nature” (L. White 1967, p. 1206). While there is definitely much truth to White’s observation of the Christian doctrine that human’s free will (voluntarism)—along with many other things he does not mention, such as their survival of bodily death—is part and parcel of some humans’ sense of separation from, and superiority to, the rest of nature, he goes on to elaborate his case against Christianity with a tendentious account of the relationship between science and technology: “But, as we now recognize, somewhat over a century ago science and technology–hitherto quite separate activities4—joined together to give mankind powers which, to judge by many of their ecological effects, are out of control. If so, Christianity bears a huge burden of guilt” (ibid.). How could Christianity be guilty for the ecological harms attributed to science? Christianity, after all, has opposed modern science from the early days when it displaced Earth from the center of the universe right down to the present day when it is replacing our divine origins with evolution and genetics.

White bases his argument on an observation that is surely correct: There was a struggle between Christianity and paganism that Christianity has more or less won. Of course, Christians do still maintain the pagan tradition of marking the winter solstice by giving gifts and decorating their domiciles with signs of the natural life that has receded in the winter and is expected to return again in the spring: bits of green foliage, red berries. A blazing fire also helps to keep the season bright. But nowadays the pagan gifts have been transformed officially into signs of Christian love. The green tree has become a Christmas tree, has an angel on top, and has been severed from its pagan roots at bottom. In White’s words: “To a Christian a tree can be no more than a physical fact” (ibid). This, as it happens, is also the scientific view of the tree. Science has no need for anything beyond the physical, in particular no need for anything spiritual, to explain the tree—and in this way happens to be in agreement with Christianity (if we ignore the issue of the tree’s ultimate origins). “The whole concept of the sacred grove is alien to Christianity and the ethos of the West. For nearly 2 millennia Christian missionaries have been chopping down sacred groves, which are idolatrous because they assume spirit in nature” (ibid).

Yes, sacred groves were cut down, the old temples were closed, along with the pagan academies of Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, and the rest. Within a few centuries the early Christians cleared Mediterranean cities of pagan temples and rites, and then over the next 1000 years expunged paganism from the rest of Europe. When vestiges of pagan practices were found still surviving during the Renaissance, witchcraft persecutions finally expurgated them by 1750, the date of the last witchcraft trial in Scotland. But, lest we forget, the Christians were not the first to engage in sacred warfare. The pagans had fought violently over the sacred groves for a millennia before the Christians began cutting them down. White neglects this fact, and denies the fact that for a Christian a tree is more than a physical fact—it is God’s handiwork, just like the sacred groves themselves—and to that extent is sacred. Nevertheless, a tree may be chopped down without the slightest stain of sin, since it has no soul of its own. This contrasts starkly with the pagan view that a tree itself could be harmed, and hence that it, or its reigning deity, must be propitiated or recompensed for its demise. For the pagan, trees shared kinship with us as living things, whereas for the Christian, trees fell on the far side of a dichotomy between us and soulless things.

Such niceties aside, however, White is mainly right about the three main claims supporting his charges against Christianity. First, modern science did have one root in natural theology. As White reports, “From the 13th century onward, up to and including Leibniz and Newton, every major scientist in effect explained his motivations in religious terms. . . . Newton seems to have regarded himself more as a theologian than as a scientist” (ibid).

Second, modern technology is partly—but only partly—explained as a result of Christians following God’s command in the first pages of the Bible: “And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” (Genesis 1:28).

Third, science and technology are powerfully allied, an alliance that really began much earlier than White says, but is nevertheless real and powerful. We have already traced the relationship between pure science and applied science in previous chapters.

Insightful though White’s account may be, it does not bear up under critical scrutiny. While Christianity helped, despite itself, to make the scientific revolution possible intellectually, it did everything in its power to suppress it. Even today, Christians are being told that Darwin is wrong and that believing in evolution is a threat to their immortal souls. They are told that prayer is physically efficacious, and that human voluntary action is free of the determining chains of physical causation. Nevertheless, despite its efforts to suppress science, Christianity made science possible by conceiving of God as the rational ruler of the entire universe in all of its domains and aspects. The rational way to rule the natural world is to design it so that it follows rational principles, or laws. The universe, since it was created by a perfectly intelligent, rational being, had logos. Both our word law and our word logic come from the Greek word logos, which carried the sense of both. In the Roman Christian context in which modern science was born, the notion of Roman law was married to the notion of God’s universal domain to yield the idea that everything that happened in the natural world (aside from the voluntary actions of men, angels, devils, or God himself) followed laws laid down for nature by God. If only we had the ingenuity to decipher these laws, we would better understand God’s wisdom.

Thus, the scientists of the Christian era were able to look at the universe with the religious conviction that it followed laws which it would be good for them to decipher or divine. White claims that every major scientist “explained his motivations in religious terms.” And so they did. But all Christians saw their entire lives in religious terms, so that is hardly an explanation of the rise of science. More relevant is the fact that God was seen as a methodological necessity by these same scientists, as they often aver and sometimes explain. One of the deepest, most concise explanations is Newton’s own in the very book that was to launch modern science. In that book Newton explains in the “General Scholium” (1687/1947, pp. 544–546) that we can deduce the laws of nature from experimental observations because God’s mind extends to every point in time and space, and thus guarantees that the same rules apply at every point in time and space.

It is for this reason that Newton famously rejects the method of hypotheses: “Hypotheses non fingo” (op. cit., p. 547). Once we have observed, for example, that the rate of acceleration is proportional to the force applied at one time and place, we know that this same relationship will hold everywhere and everywhen. Under these circumstances of a divine guarantee of the uniformity of nature, we can deduce laws from observation. It was for this reason that Newton set out his physics like a geometry text: He believes that geometry itself is an expression of just some of the principles of the natural world. He is simply adding some more axioms that will fill out the picture and enlarge our understanding of the universe around us.5 Inspired by his own success in exploring the mind of God in his handiwork, the physical universe He created, we can easily understand why Newton then ventured into theological domains, as White notes, thinking by then of himself more as a theologian than as a natural philosopher.

This brings us to another aspect of the history that White does not go into very deeply in his famous essay, although his other work leaves no doubt that he is aware of it: The roots of modern science can be traced back to ancient Greek concepts of rationality much more readily than they can be traced back to the Bible. You will find precious little in the Bible to support the idea that God is a sort of divine geometer. God is no doubt rational, but only because we think reason is a virtue and God must have every virtue. Although God gives many commandments, they are commandments of the heart, not the head. There is no commandment to be rational, although the irrational faith of children is praised and promised a reward. So, yes, White’s first premise, that modern science did have a theological root, is true. However, this root was merely the idea that God was a rational lawgiver, an idea which in turn owes much more to pagan reason and logic than it did to the Christian Bible. Christianity itself was and is profoundly suspicious of natural science, which it continues to see as a rival, and even as an expression of paganism because of its faith in the natural order or logos. The idea that nature, through a process of evolution, has sufficient creative power to create plants and animals, to say nothing of human beings, still seems idolatrous.

Much the same is true of White’s second point: that the environmental crisis (such as it is) is partly the result of the Christian belief that God commanded them to “subdue” the Earth. This is, as White himself says, only a partial explanation. In fact, the actual biblical passage (Genesis 1:28) commands us to “. . . be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.” Replenishing the Earth sounds like an ecological command. The very next verse says: “And God said, Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat” (Genesis 1:29). In other words, we are commanded to be vegetarians—just as so many environmentalists urge us to be (in fact, we are restricted to only certain plants, those bearing seeds). So perhaps when White blames Christianity for the ecological crisis, the blame is partial in another sense, namely that it is not impartial.

On the other hand, White is on to something when he points out that for Christians, living things are not portrayed as divine by their very nature. This removes a barrier to their use which was there for the pagans. On the other hand, unlike the pagan religions, Christian religions explicitly teach that greed, envy, lust, and gluttony are cardinal sins, or vices. Humans are told that the virtuous life is not one of consumption, and that giving priority to satisfying our animal drives is a deadly sin. There is no Christian license to subdue the Earth in order to drive a big automobile or have a cottage at the beach. Instead of a Christian approval of environmental misuse, there is a broad agreement between environmental ethics and Christian ethics in these matters. For Christians, driving a big gas-guzzling car is seen as an expression of greed. Rather than drive a big car, you should drive a small car and spend the savings feeding the poor.

So White’s accusation of environmental sinfulness against the Christians is un- sound. He says we live in a thoroughly Christian mindset, even when we feel we are being scientific, or post-Christian, and he has perhaps unwittingly exemplified this in his own argument, which is all about assigning guilt. Guilt is a matter of values, just as much as it is a matter of facts, and values lie beyond the purview of science. And when it comes to the facts, science tells us a completely different story from White’s about why human beings degrade the environment: Human beings are driven by desires and instincts that they have acquired through the ancient process of evolution. From the scientific point of view, religion itself is just another product of these same desires and instincts. Rather than our actions being caused by religion, science sees all of our actions, whether under the rubric of religion or under the rubric of environmentalism, as products of human nature, which in turn is a product of nature via the evolutionary process.

From the scientific point of view, it is because evolution requires us to be fruitful and multiply that we believe God has commanded us to do so. Because evolutionary success requires outcompeting other species, we have come to believe that we have a divinely sanctioned right to have dominion over them. This belief increases our evolutionary fitness. Intelligence, reason, our sense of right and wrong, all of these are themselves in service to the first and second evolutionary commandments: (1) Survive. (2) Reproduce. From this scientific point of view, the sense of the sacred that people—especially pre-scientific people—find in nature is also in service to these evolutionary commandments. Many environmental philosophers profess that wilderness is a place where one gets in touch with the sacred (Abrams 1994, Naess 1995, Snyder 1995, among others). They not only accept that such experiences are real, but believe that their content is accurate as well: The wilderness is, in fact, sacred. That they have this belief is no surprise from the scientific point of view. Whether the belief has any scientific validity or truth is another matter, however.

7.3 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND THE SACRED

It is no accident that environmental scientists in particular have gravitated to the idea that nature is sacred. Biologists especially are likely to discover—or rediscover—this natural attractor in human conceptual space. The eminent biologist, Niles Eldredge, for example, begins his recent book with the words, “If ever a place deserved our attention, even our reverence, it is the Okavango Delta” (1998, p. 2; my emphasis). He goes on to call it “the last vestige of Eden” (even though it came into existence a mere 5000 years ago, when geological changes drained a lake that previously covered its locale). Eldredge has a scientific basis for seeing this stunningly and uniquely beautiful part of the world as Eden. He believes that the Okovango Delta is “a remnant of the stage on which our own species, Homo sapiens, evolved . . . about 125,000 years ago” (p. 1). This is odd, given that the sacred Okavango came into existence only 5000 years ago, according to Eldredge himself. It didn’t exist when our species evolved, when conditions at the Okavango Delta, as elsewhere, must have been very different. Ice gripped the Earth 125,000 years ago, which according to current scientific knowledge rendered the Okavango arid and barren.

If, perhaps, Eldredge leads with his heart rather than his head when it comes to the beauty of the Okavango, we at least have a scientific explanation: It is filled with possibilities for finding the sorts of food, clothing, and shelter that Homo sapiens instincts were honed by evolution to find. It is filled with fish, fowl, and game. Although Eldredge would find the idea of sport hunters descending on the Okavango abhorrent, he is driven by the very same sense of beauty as they are. I have never met a sport fisher or hunter who did not see his activity in the light of the sacred. Sport fishers and hunters do not hunt for food but to get in touch with the beauty of nature and—taking a turn that offends many modern sensibilities—to relate to that beauty in a way that they find restorative and a blessing. They hate what they call the rat race. That is why they get up before dawn to sit in a boat holding a line and slapping mosquitoes while awaiting the rising sun. They would pay big bucks—they would kill, as the expression goes—to do this in the Okavango.

Eldredge has sublimated this primal desire while still leaving himself open to the sense of beauty it evokes. Like a man admiring a Renoir nude, he is almost beside himself with the chaste but tantalizing joy this evokes. And, to get to the most important point, it is the power of modern science that makes his refined sense of beauty possible. Therefore, Eldredge’s sense of the sacred is also rooted in the Christian hypothesis that God (with a capital G) ordered the natural world by natural law. Natural law was enacted by God through His divine command. As Galileo put it in his famous letter to the Grand Duchess Christina (1615), God is the author of both the book of revealed truth and the book of nature. So they cannot contradict. And God, moreover, had shown himself to be the most exquisite and sensitive geometer. The princess was not convinced, however. Her Bible told her that Joshua commanded the sun to stand still, which was proof enough it had to be moving in the first place, so she resisted Galileo’s heretical sophistry.

Putting aside this early enmity between science and religion, we can plainly see here another root of Eldredge’s sense of the sacredness of nature. It owes just as much to Pythagoras and Euclid and the natural philosophers they inspired as it does to the Christian Bible. The fathers of the scientific revolution, the great Polish astronomer Copernicus, the great French mathematician Descartes, the great Italian physicist Galileo, and the great English mathematician Newton called themselves philosophers of nature. They were—of course!—Christian philosophers. But they were philosophers nonetheless, who knew Euclid’s Elements of geometry every bit as well as they knew their Genesis. They believed in God, the rational creator of a world ordered by natural law. It is another two centuries later that they become known as “scientists,” during the marriage of science and technology that White brings to our attention.

Newton, Galileo, and the rest are the intellectual ancestors of the American biologists Niles Eldredge and E. O. Wilson, both of whom believe in the sacredness of nature. They rely on reason to understand the way the world is, and in their minds it is reason that convicts humankind of its environmental sinfulness. It is their scientific understanding not only of the way the world is, but their realization that it is startlingly different from the way that it was, that gives them the idea of a new and looming apocalypse, environmental apocalypse. In this apocalypse, nature will smite us. In the words of White (whose publication in Science may perhaps be the scientific equivalent of the publication of a papal bull), the approaching environmental apocalypse will be in the form of a “disastrous ecological backlash” (L. White 1967, p. 1206). We are hurting nature, and nature will hurt us back, in an ecosystemic version of natural justice.

And lest scientists think that they can avoid the coming apocalypse all on their own, White warns against such arrogance: “I personally doubt that the disastrous ecological backlash can be avoided simply by applying to our problems more science and more technology” (ibid.). It is at this point White is clearly assuming the tone of religious prophecy: He is warning scientists not to play god! He goes on to instruct them that “since the roots of our trouble are so largely religious, the remedy must also be essentially religious, whether we call it that or not. We must rethink and refeel our nature and destiny” (1967, p. 1207). Most important, White warns us we must “reject the Christian axiom that nature has no reason for existence save to serve man” (ibid.).

We should reject this axiom, but not on religious grounds. White’s argument that the remedy to our environmental problems must be religious is a glaring nonsequitur: It does not follow that if the roots of a problem are of a certain sort that its solution must also be of that sort. The roots of a family’s problems may be substance abuse, but it hardly follows that more substance abuse will solve those problems; the roots of an auto accident may be automotive (such as brake failure), but its remedy may be medical (such as emergency surgery). Whether or not religion is at the root of our environmental problems, a solution to our problems must, as always, begin with knowledge and understanding. Of course, nature does not exist to serve us, for Homo sapiens is merely part of a greater biological system from which we have arisen and upon which we depend for our existence. We owe everything to nature; it owes nothing to us—the reverse of the axiom White rightly calls upon us to reject.

There is no doubt, however, that environmental science conceives and expresses humankind’s relationship to nature in a manner that is—as a matter of observable fact—religious. Environmental science prophesies an environmental apocalypse. It tells us that the reason we confront apocalypse is our own environmental sinfulness. Our sin is one of impurity: We have fouled a pure, “pristine” nature with our dirty household and industrial wastes. The apocalypse will take the form of an environ- mental backlash, a payback for our sins. “Vengeance is mine” says the environment. We are warned not to “play God,” not to seek a scientific techno-fix to postpone the day of reckoning. Instead, we must repent. We must stop our polluting ways, which are merely the expressions of our materialism and our greed (which itself springs from our lust, envy, and pride). We are to reject our greed for modesty, exchange our pride for humility, and respectfully return to our own proper eco-niche within the greater ecosystem. These exhortations are inscribed in textbooks of environmental science (as we have seen in Chapters 4, 5, and 6). And so it has come to pass that environmental scientists have taken on the role of the priests of environmentalism. Just as four centuries ago priests in black robes explained the sacred mysteries of God to lay persons incapable of judging for themselves, so today scientists in white lab coats explain the sacred mysteries of nature to citizens incapable of judging for themselves. And just as priests then told people what they must do to be blameless before God, today environmental scientists tell people what they must do to be blameless before nature (cf. Foss 2006).

7.4 BEYOND ENVIRONMENTAL RELIGIOSITY

On the face of it, the appropriation of the idiom of the sacred by environmental scientists may seem like a benign thing, or at least an innocuous thing. Sure, it is interesting from an intellectual point of view that environmentalists have employed the idiom of religion—but what is the harm? One problem is that the identification of the sacred licenses the broadest range of ethically permissible actions. What is sacred can be, indeed must be, protected at all costs. The concept of the sacred gives emotional substance to the transcendent value at the heart of an ideology. This does not automatically entail any harm, but it does immediately create the risk of harm. The environmental scientist speaks with priestly authority to lay environmentalists who will draw conclusions for themselves and undertake to protect the sacred on their own. We must not forget that environmentalists both scientific and lay see nature as in a state of crisis, as under an ongoing attack by the human species itself. When the sacred is attacked, some response, some counterattack, is required. Attacks on the sacred are sacrilege. Just what form a response to sacrilege takes depends on a great many other things, such as the emotional state of those responding, and, crucially, their other beliefs. The response depends, in large measure, on just what other things are thought sacred: in particular, whether human beings are seen as sacred. If humans are seen as sacred, this rules against their sacrifice for the good of the environment. Sad to say, environmentalists typically do not see human beings as natural, and environmentalists always demand that human interests be sacrificed for those of the environment.

This new form of environmental doctrine is plainly a marriage of convenience between elements that do not really belong together. On the one hand, there is science and reason illuminating the current state of nature, showing us what we have done wrong so far, and forecasting how these wrongs will ramify apocalyptically in the future. On the other hand, the guilt for environmental destruction (or is it environmental sacrilege?) also falls largely upon science in its technological role, with the result that environmental scientists themselves say that the solution is not, in White’s words (1967, p. 1206), “more science and more technology.” Science is above suspicion as long as it confirms our guilt, but it is not to be trusted with anything to do with expiation of that guilt. We have poked our fingers into the sacred machinery of nature and are being told not to do it again.

As noted in the introduction, environmentalism is a popular movement, so we should not be surprised to find coalitions of convenience on both the practical and the theoretical planes. We lack terms for the current concatenation of elements. It is a sort of neoscientific religion in which the sacredness of nature has replaced the divinity of god, and the reading of environmental omens via scientific measurements has replaced the reading of the Bible. It is equally a sort of neoreligious science, in which the service of nature has replaced the service of truth, and reversing technological intrusions into nature has replaced increasing the power of scientific knowledge. In any case, we need something better if humankind is to see its way to a better relationship with nature. There is absolutely nothing wrong with scientists bringing their professional expertise to bear upon the question of the sacredness of nature. The problem is that their professional expertise does not go beyond the facts as such, whereas the sacredness of nature does. What we take to be sacred is indeed a function of the facts as we see them, but taking something to be sacred is also to adopt an evaluative stance toward it. Scientists do not have any professional expertise when it comes to values—but then, who does? Religious authorities, perhaps? Fortunately, we do not need to answer the question of who the proper moral authorities are in order to move forward philosophically.

Let us move beyond science and religion, directly to the matter of authority itself, which we may approach via the distinction between believing and believing in. Someone believes something when they really think it is true, whereas they believe in something when they accept it as true despite reasons to doubt its truth. For example, people believe that Earth is round, or that the toaster requires electricity to work, or that it is raining, because there are no reasons to doubt these things. On the other hand, people believe in flying saucers, or believe in reincarnation, or believe in taking vitamin C to fight colds, which means that they know there are reasons to doubt their truth, but they choose to believe them anyway. Where evidence and logic are insufficient to justify belief, people will nevertheless often exercise what they take to be a legitimate option: believing something because they want to or think they should. The nature of the supposed legitimacy of believing in is partly legal: Democratic countries generally guarantee “freedom of belief.” In any case, people will believe things that relieve the painfulness of life’s difficulties. A mother whose son or daughter was listed as missing in action in a foreign war may choose to believe that he or she is still alive, despite much evidence to the contrary.

It is true that people in democratic countries generally have the right to believe in whatever they like whenever they like and for any reason they choose. Freedom of belief is a good thing, because its opposite, belief control, leads to despotism and stifles the freedom of thought and openmindedness needed for humankind to gain knowledge and advance understanding. On the other hand, believing in is not always, or even usually, a good thing. In fact, it is generally a bad thing to believe something for any reason other than the high probability of its truth—and even then, it is better merely to believe that the probability of its truth is high. Proportioning belief to evidence and argument is a key tenet of Western philosophy. Sometimes this can be painful; sometimes it takes courage. However, it has also proven itself as the best way to acquire knowledge and understanding. Within science, it has enabled us to solve some of the key mysteries of nature. Within law, it has enabled us to solve crimes and attain a level of justice. Within philosophy, we must avoid believing in altogether, since philosophy seeks truth and understanding as the basis of wisdom. In other words, no claim, whether it concerns facts or values, is to be judged acceptable on the basis that we believe in it. In yet other words, all claims are to be subject to logical criticism.

If you are among the hundreds of millions of city dwellers who have been required by law to recycle tin cans, bottles, and other items, rather than putting them in the trash, you might take a moment to consider what you are doing. Let us consider the cases for and against.

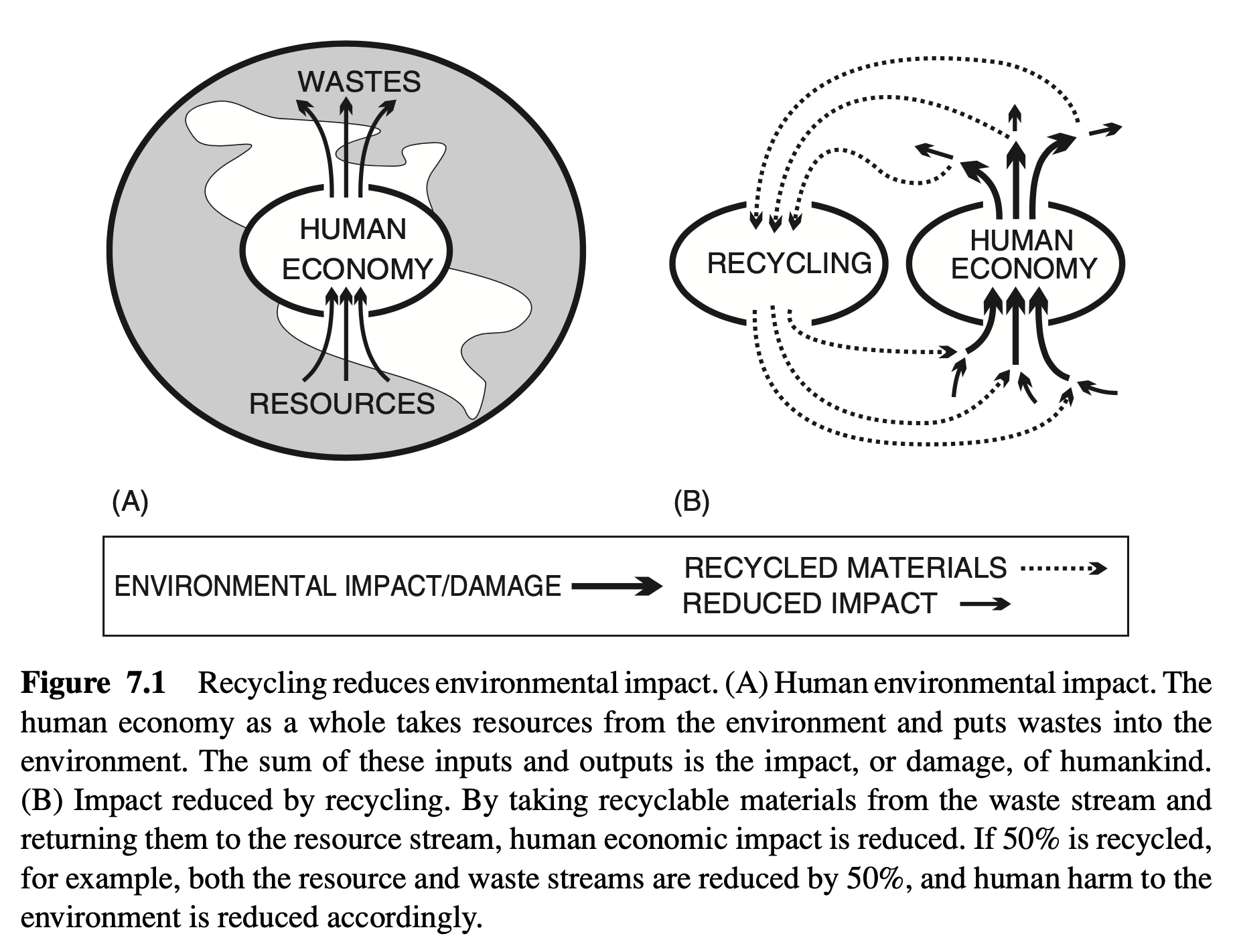

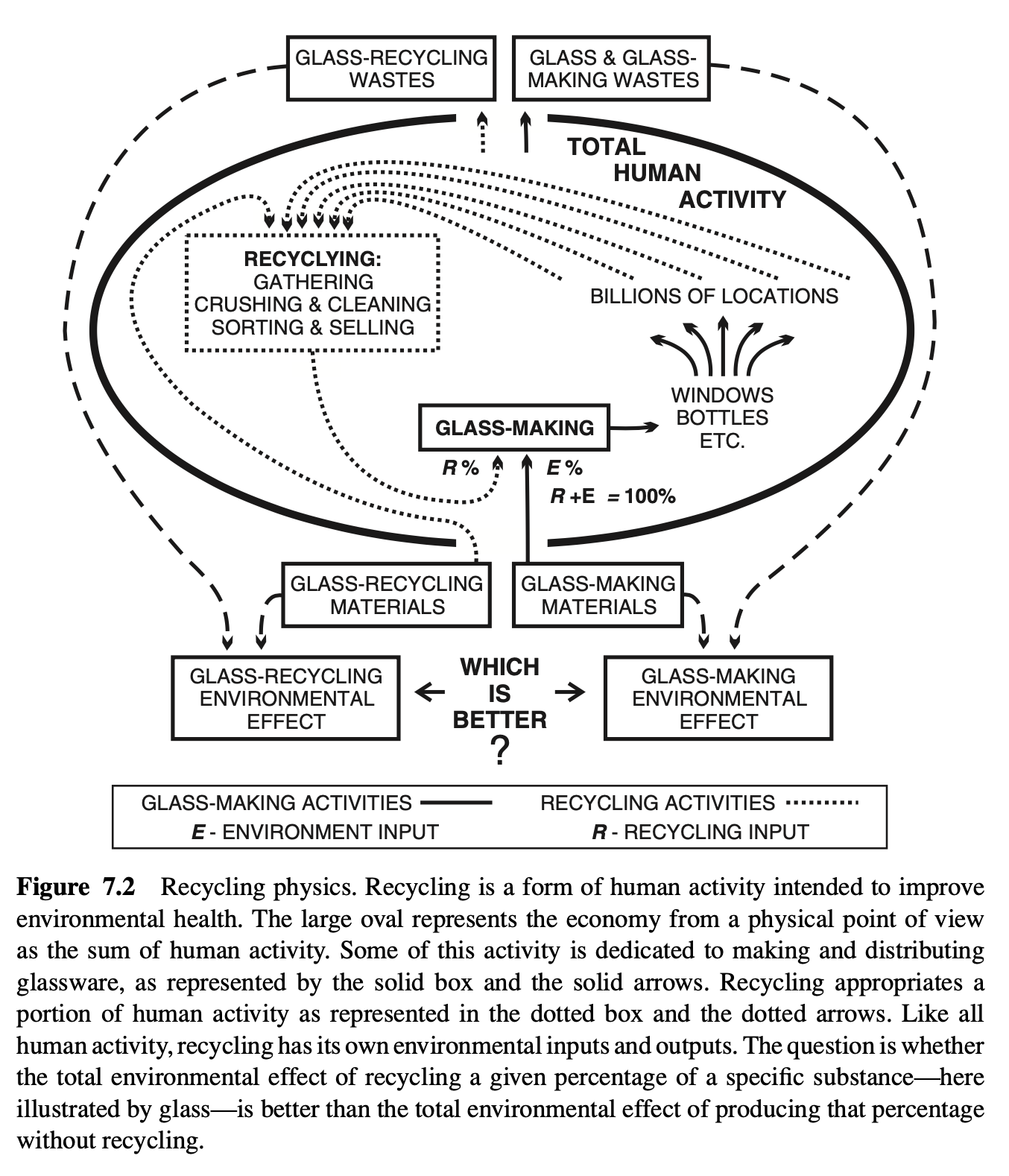

Environmentalist Recycler: Recycling is good both for the environment and for humankind. It is a win–win activity. The total of human economic activity results in the total environmental impact shown in Figure 7.1A. Ultimately the environmental damage due to human economic activity will come back to damage human beings as well, because the current pattern of continuous economic growth means constantly increasing environmental impact, and that increase is not sustainable forever. As many environmentalists have famously pointed out, the only thing in nature that follows a policy of continuous growth is cancer. Continuous economic growth implies that

humans are like a cancer growing on Mother Earth. The ability of the environment to provide resources on the one hand, and to absorb wastes on the other, is obviously finite, so obviously we have no choice but to reduce our environmental impact. As shown in Figure 7.1B, recycling reduces the amount of raw materials and energy that must be extracted from the environment. Recycling also reduces the flow of garbage into landfills. Landfills are bad for the environment in a number of ways: landfills remove land from ecosystems, reducing the available habitat for animals and plants; landfills pollute surface water and groundwater through their formation of leachate, water polluted with bacteria, heavy metals, various chemicals, and so on; landfills pollute the atmosphere through the formation of the greenhouse gas, such as methane.

We know that re-melting aluminum cans uses less energy than making the same amount of aluminum from aluminum ore. As this case shows, recycling reduces resource and energy use, reduces the GHGs released into the environment, and reduces the amount of land used for mining and for waste disposal. This in turn moves us toward sustainability, which is good for us as well as the environment. Thus, recycling is a win–win proposition, a no-brainer. We obviously need to recycle for our good and the good of the environment.

Post-environmentalist: The picture you paint begins with a fundamental error: You portray recycling as though it were outside the human economy, but in reality recycling is part of the economy. As shown in Figure 7.2, recycling has the same essential characteristics of all economic or organic processes: It takes materials from

the environment and ultimately returns them to the environment as waste products. For concreteness, Figure 7.2 focuses on glass recycling, although it illustrates the physics of recycling in general. One thing it shows about the case of aluminum cans is that the mere fact that re-melting them takes less energy than making aluminum from the ore does not demonstrate that recycling aluminum cans has a smaller environmental effect (or impact) than aluminum mining and smelting. We cannot ignore the fact that recycling aluminum cans, just like any other form of human activity, makes many demands on the environment, including the demand for energy.

Household recycling of metal cans, bottles, and other containers begins with rinsing or washing the used container. Flyers, brochures, and television advertising are purchased by government recycling agencies to tell citizens they must recycle various items, including cans, bottles, and plastic containers, and that these items must be washed before they are placed in curbside containers for collection. This use of advertising not only proves that recycling is a business like any other, but places a demand on the environment for the washing of used containers that it legislates. Not only are citizens required to wash thousands of tons of discarded containers, but these waste materials usually have to be washed a second time before they can actually be reused. All of this washing requires water, energy to warm the water, detergent, and so on. Disposal of the resulting dirty water at sewage treatment plants also uses energy and materials, as well as land, air, and water resources.

Once the used containers are washed and put at the curbside, people must drive trucks to collect these recyclables, which burns fuel and emits GHGs into the atmosphere. It also requires all of the resources, energy, GHG emissions, and waste disposal involved in the production and maintenance of the truck fleets used in recycling, their tires, their fuel, and so on. These fleets also are responsible for a portion of the resources used in maintaining the road system. Recycling also requires facilities, such as parking lots for the truck fleets, buildings where the old containers are taken to be sorted, washed, crushed, stored, and so on, which requires land, resources, energy, and waste removal. There are tens of thousands of these facilities around the world.

Does the portion of these facilities dedicated to, for example, glass recycling actually take less land and energy than the pits used to provide the same amount of glassmaking sand? We simply do not know. On the face of it, collecting all of the used bottles and grinding them back into sand again seems like a very high cost way of getting glassmaking materials, and high cost usually indicates greater demands on resources and, hence, on the environment. Moreover, the energy required to melt recycled glass is about the same as that used to make glass from other materials.

We must not forget the people involved—citizens like us—whose labor is required to make recycling happen. All of the people involved in the recycling process, from the citizens who take time to sort, wash, and prepare their wastes for recycling, through to the workers who collect, prepare, and distribute them to the reusers, also make demands on the environment for their food, clothing, and shelter. From the physical point of view, recycling requires human activity, which in turn requires environmental inputs and outputs just like any other biological activity. When recycling workers spend their wages, they make demands on the environment that are an essential part of the environmental cost of recycling. While a person is busy working to recycle some item, they are metabolizing their food, wearing out their clothes, expending their shelter, and so on. Other human activity will be required to provide this necessary input into the recycling process.

Until the total of all these environmental impacts of recycling are shown to be less than the environmental impact of using new material, we have no reason to suppose that recycling of any given material reduces environmental impact. We cannot simply assume that recycling will have a smaller environmental impact, no matter what environmentalist sloganeering may have led us to believe. As illustrated in Figure 7.2, recycling reduces the amount of glassmaking materials taken from the environment by a certain percentage (R%) and reduces glass and glassmaking wastes by a similar amount. What is generally overlooked is that recycling also requires other materials to be taken from the environment and creates its own wastes. If recycling glass were good for the environment, the decrease in environmental impact (by roughly R%) would have to be more significant than the increased impact caused by recycling itself.

But this has never been shown. It has not been shown for glass or for the other materials that are recycled. Indeed (as we shall see in more detail below), we have good reason to believe that there is no overall reduction in environmental impact; otherwise, recycling would be done automatically out of a profit motive. Therefore, we are being forced to recycle on the basis of faith, not reason. So recycling is an environmentalist form of ritualized penance (cf. Foss 2006).

Environmentalist Recycler: Of course, recycling redirects a certain amount of human economic activity away from extracting materials from the planet or dumping materials back into it. That is the whole point. No one ever said that recycling would be profitable from an economic point of view, since that is not its objective. Certainly, recycling requires significant numbers of people to expend time and work in pursuit of sustainability, but that is a price well worth paying both for the environment and for future human beings. You are merely being cynical to suppose that the environmental impact of recycling might be greater than the environmental impact of using new materials.

Post-environmentalist: I am not supposing anything. It is the environmentalist who is making the assumptions here. The universal mantra of the environmentalist, “reuse, recycle, reduce,” assumes that the environmental impact of recycling a material must be smaller than the environmental impact of using new materials. There is no mechanism or invisible hand that will guarantee this assumption. For all we know, it may be true in some cases, and false in others. The crucial point is that it has never been shown for any material—indeed, no serious effort has ever been made to even investigate the issue fully. City councils and other levels of government have commanded citizens to recycle without ever knowing whether it does in fact reduce our environmental impact, moved solely by the command to recycle that they have heard since the 1980s. Citizens have called for and supported these laws while in a state of ignorance about their actual environmental effects. It is environmentalist faith, therefore, not reason, which is behind recycling.

Environmentalist Recycler: You have completely ignored the question of sustain- ability. And you have also overlooked the fact that recycling is still at a fairly primitive stage, since at this point only a relatively small percentage of materials are recycled. In Figure 7.2, we must understand that R, the percentage of recycled materials, is rel- atively small compared to E, the percentage of materials taken from the environment. Until R is closer to 100, and E is closer to zero, the true potential of recycling will not be realized. At this point it is important to keep the recycling initiatives going, so that economies of scale can eventually be achieved. We look forward to the day when recycling technologies, plants, processes, and so on, have become sophisticated and standardized, and will routinely reduce our environmental impact. We can even dare to envision a day when virtually all of the materials we use are recycled and our environmental impact is reduced nearly to zero. Until that day arrives, we must keep pressing forward with recycling initiatives.

Post-environmentalist: Pushing forward without any assurance that your goal is achievable or worthwhile is just the stuff of faith, not reason. When it comes to sustainability, no one has ever shown that we will run out of materials for making containers, newspapers, or packages. Long before we run out of glassmaking sand, we will almost certainly quit using glass to make containers in favor of cheaper plastics or other materials not yet conceived. Nor has anyone ever shown that we will run out of iron with which to make tins, or fiber to make paper, or bauxite to make aluminum. In fact, none of the materials involved in legally enforced household recycling is in any danger of depletion. These materials are being used precisely because they are plentiful. The bigger likelihood is that we will move on to better packaging technology and better information technology long before we run out of the materials used in the current technologies. To say that our use of these materials is unsustainable is merely to recite another unproven article of the environmentalist faith.

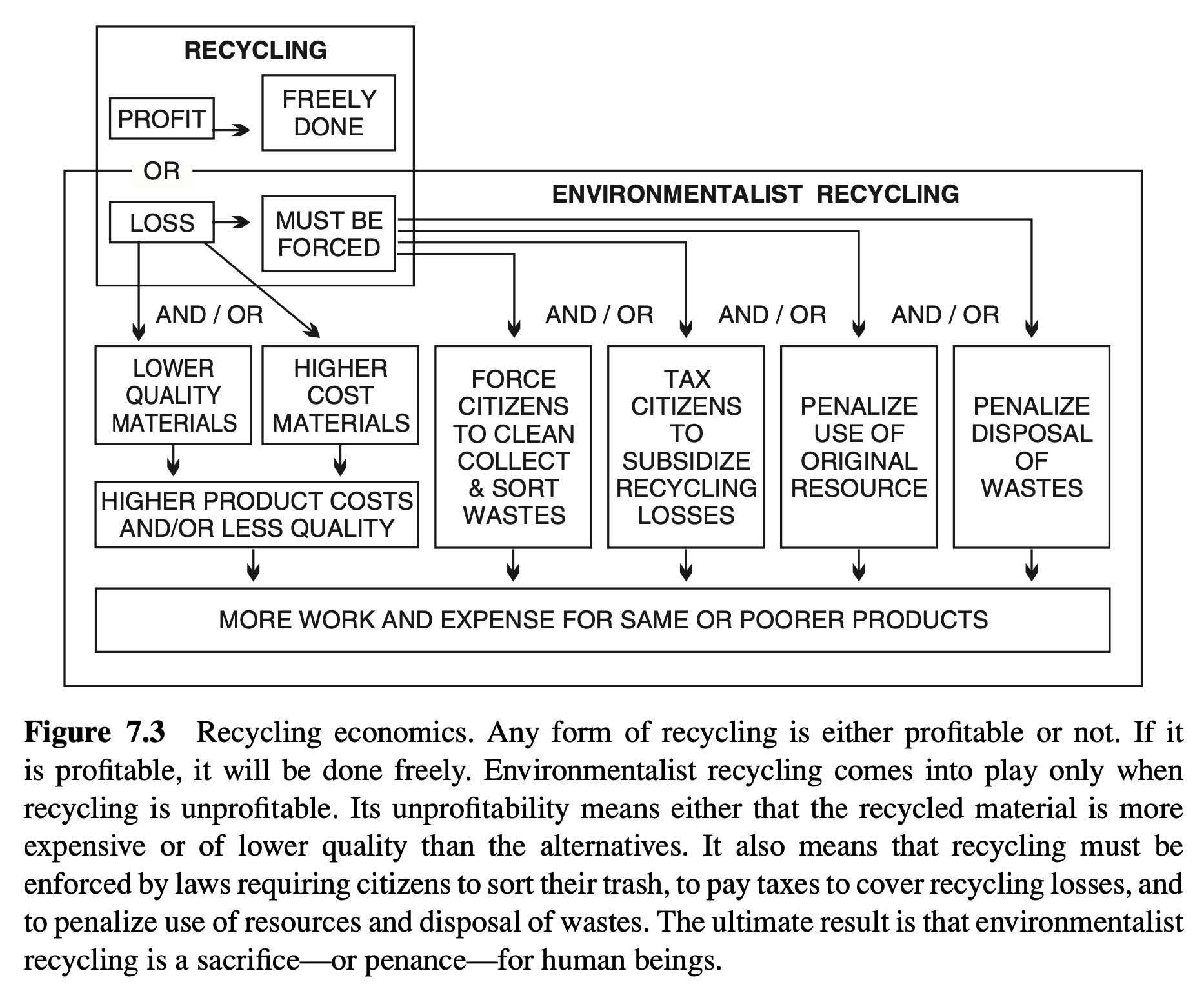

Environmentalist recycling is based on two assumptions: first, that recycling will be good for the environment, and second that it will be good for human beings. Note well that these are value claims, and hence not open to proof or disproof, although they are open to logical investigation. The scope and difficulty of these assumptions is illustrated in Figure 7.3. Recycling either is profitable in economic terms, or it is not.

Where it is profitable, no other incentives are required to implement it, and it will be done out of the profit motive. There are countless examples of this sort of recycling. For example, people who fabricate sealed window units must cut plate glass to the various sizes required for their products. The pieces of glass that are trimmed away are usually returned to the glassmaker for a profit. The glass trimmings are clean, all of the same sort, and so on, so need no washing and sorting, unlike the case with environmentalist recycling. Window fabricating businesses tend to be located close to glassmakers, and vice versa, in order to benefit from lower transportation costs, which in turn increases the cost-effectiveness of recycling the trimmings. Indeed, window fabricating and glassmaking occur under the same building in most modern plants, so the glass trimmings need merely be taken from the end of the assembly line back to the beginning to be recycled and reused.

Environmentalist recycling comes into play only when recycling is not profitable, but this very fact militates strongly against it being good for human beings or good for the environment. The fact that environmentalist recycling operates at an economic loss implies that either the commodity it produces (recycles) is of lower quality than the original product, or else it costs more, or both. Both of these are negative factors from the human point of view. Glass recycling, for instance, yields a dirty mixture of different sorts of glass. Hundreds of grades and colors of glass are manufactured to meet the technical specifications of manufacturers. Since it is virtually impossible to sort all of the recycled glass into these hundreds of sorts once again, it is generally sorted into two or three gross categories: brown, green, and clear, for instance.

Moreover, since no recycling occurs until the glass is actually reused for some purpose or other, and since recycled glass is of low quality from the glassmaker’s point of view, people have to be paid in many cases to accept the dirty and ill-sorted glass in what are called materials recovery facilities (MRFs). In the newspeak of environmentalist recycling, these facilities pay a “negative price” for recycled glass to cover their costs to clean, sort, and process it further to make it acceptable to some manufacturer. The concept of negative price is nicely explained in a document produced by The City of New York Department of Sanitation. “Ideally, municipalities sell recyclables, and processors (MRFs) buy recyclables. Yet when the market value of certain commodities falls to zero, MRFs are not willing to buy these materials. Under free market conditions, zero-value commodities would simply be disposed of as refuse” (DSNY 2004, p. 19). To put it bluntly, the materials we recycle are in many cases of zero-value, that is, of no value whatever, to the very industries that are supposed to recycle them. In fact, recyclables may be of less than zero-value, that is, have a negative value. The rational thing to do with such materials is dispose of them. “But municipalities with recycling laws or mandates can’t just do this—they are required to recycle certain materials, no matter what. In such cases, municipalities ‘sell’ these materials for a negative price. In other words, they pay processing firms to take them” (ibid.).

As shown in Figure 7.3, taxes must be collected to pay processing firms to accept recycled materials. Taxes are hardly a benefit for the citizen. Other forces are also used by governments to make recycling happen despite its unprofitability. One is to legally require citizens to do the primary sorting, cleaning, and preparation of the materials to be recycled. This work is not a pleasure in and of itself, although some environmentalists may feel a righteous joy in doing it because of its intended—but unproven—effects. Raising punitive taxes, fees, or fines against the usual resources and waste disposal methods also encourages recycling by making the usual methods of production more expensive. Again, this is nothing but a loss from the point of view of the ordinary citizen. As if this was not bad enough, the products made from recycled materials are apt to be of lower quality as well, since the lower quality of recycled materials is one of the main reasons they are recycled at a loss—or if you prefer, at a negative profit.

Nor is the issue of the relative percentage of materials recycled an argument in favor of recycling. Contrary to what you dare envision, we know on basic physical principles that it is impossible that all of the materials needed for life can be recycled. Life physically requires that materials both be taken from the environment and returned to the environment.6 However, it is possible that the percentage of a specific material that is recycled may approach 100%. For the sake of concreteness, let us suppose that the percentage of glass that is recycled has been brought from 10% to 100%. Given that there was an economic loss, a loss of money, labor, time, and product quality when only 10% of glass was recycled, this loss will increase at least tenfold when this percentage is increased tenfold. In fact, moving beyond the first 10% of glass that is relatively easily recycled to the last 10% that will be difficult to recycle makes a projected tenfold increase in our collective loss much too optimistic.

If we assume that nothing else changes in the economy except for the redirection of some work and money toward environmentalist-mandated recycling, there is less work and money available for the other things we need or want, so we are collectively worse off all around. So it is just plain false that recycling is good for those of us living today. As we have seen, the claim that it will be better for future generations because it is more sustainable has never been shown. In fact, the only way that recycling will not make us all collectively poorer is if additional economic activity is employed to make up for the labor and money directed into recycling.

So in the end, we are asked to make sacrifices in order to avoid the often-prophesied environmental apocalypse, even though there is no clear understanding of how our sacrifices are supposed to reduce our environmental impact. Environmentalist recycling, therefore, is nothing other than ritualized penance.

Environmentalist Recycler: So your supposed solution is business as usual. Are you denying that the capacity of the environment to provide resources and absorb wastes is finite? Are you not aware that continuous economic growth is therefore unsustainable?

Post-environmentalist: Are you not aware that continuous economic growth does not imply continuous increase in the amount of materials we take from or return to the environment? Continuous economic growth refers to growth in value, not in physical bulk. We are surrounded by items of small bulk but high value: cell phones, computers, music players, etc. Yes, Earth is finite, but so are we. There is no danger that we will one day need an infinite supply of materials to accommodate our finite human activities. Anyway, the total human population will soon begin to decrease (see Figure I.1 in the Introduction) and that leads us toward decreasing environmental impact. Speaking of trends, should we be afraid that humankind itself is “unsustainable” just because fertility rates are trending downward? Surely not, which shows that extrapolating trends to their furthest possible extent is logically naive.

Environmentalist Recycler: Perhaps your faith in humankind is naive. In any case, you have implicitly granted a point that is on my side of this issue: that we should be looking for greater value in ways that do not make ever greater demands on our environment.

Post-environmentalist: Agreed. In the end, value is what this issue is all about. So the question comes down to this, as illustrated in Figure 7.2: Is recycling better all around, both for us and the environment? Or is it just a penance?

7.5 THE NATURALLY SACRED

The sacred has always been associated with the supernatural. Because the supernatural is, by definition, completely beyond human comprehension, it is necessarily shrouded in darkness and mystery. So the sacred, rather than being essentially a source of light and understanding, has been equally the source of much trouble in human history. Because the supernatural is a matter of believing in, it has been subject to dogmatism and abuse, including such things as despotism and wars of religion. To the extent that environmentalism involves believing in the sacredness of nature, it, too, is cognitively impenetrable and open to dogmatism and abuse. Fortunately, we do not need to indulge in believing in the sacred in order to accept that nature is sacred. First, we can recognize that humankind finds nature sacred. Second, we can recognize that it is perfectly rational for us to do so. The conjunction of these two realizations is a concept that we may call the naturally sacred.

For untold millennia, human beings have in various ways realized that they are themselves a product of the natural world and that they depend on it for their existence, as do all living things. The source and ground of humankind and life itself is naturally seen as sacred. Science has confirmed this ancient realization by discovering many of the details of the emergence of life and humankind on Earth, as well as the details of the processes of metabolic chemistry whereby life is maintained. Properly understood, this new scientific realization does not in any way reduce life’s value, beauty, and awe. We observe that consciousness and life itself come to us directly from nature, regardless of whatever we may speculate lies hidden behind what we can see. The former is a matter of belief, the latter a matter of believing in. Thus, it is a matter of belief that nature is a focus of positive value, beauty, and awe, other essential characteristics of the sacred. Given that we humans value our own lives, it follows that we value their source and their sustenance. Now that science has confirmed in detail how nature has created us, we recognize its value in more detail than before. It is beyond precious, being the source of value of anything within it.

Similarly, science increases the beauty and awe of nature. Whether we observe the countless galaxies wheeling through space or the microcosm of the living cell, we are struck by the beauty and power of the natural world. Scientific understanding of natural processes does not diminish this beauty but enlarges it. And since every mystery resolved is resolved by revealing yet further mysteries, nature remains mysterious, another aspect of the sacred. Indeed, scientific understanding adds texture and depth to the mystery. Respect for nature is a natural consequence of its value, beauty, awe, and mystery. Awe is the mirror image of beauty; beauty and awe are the opposite ends of one dimension of human sensibility. Whereas things of beauty instill desire, things of awe instill fear. Beauty floods at birth and ebbs in death, while awe does the opposite. Beauty is found in flowered valleys, awe is found in glacial mountain peaks. Together they create a tension that we call sacred, and that instills respect.

It is perfectly rational to find nature sacred in the sense just described. Indeed, the aspects of nature outlined in the previous two paragraphs effectively define the sacred: the source and ground of our existence; a higher order of value; a focus of beauty, awe, and mystery. The naturally sacred is not something to believe in but something that can be recognized by humans. The description of the naturally sacred is a description of what human beings find sacred. The thesis that we, humankind, find nature sacred is to be understood as a type truth.

No doubt some people have no sensibility of the beauty of nature. Certainly, some people find neither beauty nor awe in wilderness. All it takes is a single weekend being “eaten alive” by insects to put some people off wilderness for a lifetime. And almost no one finds value, beauty, or awe in being bitten by insects. Nevertheless, even people who do not like wilderness often love nature just the same. Many people love their pets, a very common human expression of their recognition of value and beauty beyond their own species and its advantage in the struggle for survival. Almost every human home has plants within, under the roof, sheltered from harm as if they were kin, and similarly watered and fed, even doctored. Regardless of whether they find wilderness, nonhuman animals, or plants, virtually all people experience the sacred in the organic realities of life, birth, death, and love. Life flows through us in all of its exquisite complexity, as desire, fear, joy, pain, love, hatred, birth, and death. Despite this, there are some people sadly unable to appreciate the value, beauty, awe, and mystery of life and nature, just as there are some tigers that cannot outrun a human being. Nevertheless, it is a type truth that human beings experience the naturally sacred.

Trying to define the naturally sacred is a little bit like trying to reduce the wonder of existence to a formula. However, it is important for the philosophy of nature that we at least have a working definition, an epigrammatic formula to guide our efforts. I suggest a three-part definition:

- The cognitive core of the naturally sacred is our recognition of the fact that nature is the source and basis of our existence.

- The evaluative core of the naturally sacred is our sense that nature is worthy of our respect. Of course, no fact entails any value, but given that we see that nature has produced us and supports us, and assuming we have some self-respect, this urges us to respect nature as well.

- The emotive expression of the naturally sacred is our sense of the beauty and awe of nature. People often confuse respect with fear, and will say, for example, that bears deserve your respect merely because bears are dreadfully dangerous. To truly respect a bear you must see it as in some way admirable. Both beauty and awe are admirable, and while awe inspires fear, it also inspires respect because it is also admirable. The cognitive, evaluative, and emotive cores of the naturally sacred form a rational whole. It is rational to feel respect, which is itself a blend of admiration and fear, for the beauty and awe of nature, given that it is the source and basis of our being.8

IS ACCEPTING RESPONSIBILITY FOR NATURE SACRILEGIOUS?

That we should accept responsibility for the health and well-being of nature is one major thesis of this book. There are four reasons for this. First, it is undeniable that humankind has had large-scale effects on nature. These effects began long ago, when we lived much closer to nature in a state idealized by many environmentalists. It seems likely that our ancient hunter-gatherer ancestors played a role in many of the extinctions of game species, such as the woolly mammoth and other species of Pleistocene megafauna. We know from the remains of these animals that they were hunted by our species and that they disappeared from their natural ranges shortly after our species arrived in those locales. Our effects accelerated when we turned to agriculture, and significantly large portions of Earth’s surface were cleared and plowed for our crops. And, as we have so often been reminded, our impact continues to this day. Second, we are capable of understanding nature well enough to appreciate whether these effects are good or bad not only for us but for living things in general. This is presupposed by environmentalists whenever they identify any form of environmental damage or suggest a remedy. If we accept, for instance, that dumping toxins in rivers has a bad effect on living things, we accept that we have the capacity to appreciate what is good or bad for living things. Third, we therefore have the power to effect large-scale good or harm for nature as a whole. Fourth, we are the only species with this understanding and power. It follows, therefore, that we have a large-scale responsibility for the wellbeing of nature as a whole. Developing this argument will be one task for the rest of the book.

The toughest obstacle to accepting responsibility for nature will be the objection that we should not “play God.” This is just one form of the idea that the sacred is to be left alone, that not leaving it alone is sacrilege. But since it is the strongest form, if we can lay it to rest, the other forms will be rebutted as well. The presupposition behind the warning not to play God is that God is responsible for nature, and taking this responsibility from God is arrogance, or the sin of pride. I sympathize with the humility and self-doubt that this attitude represents. Nature is, after all, filled with awe. It can extract an awe-full toll should it so decide, as floods, pestilence, plague, and famine have testified since the dawn of history—not to mention the meteorites and comets that have collided with Earth in prehistoric times. Still, the awe-fullness of nature does not justify rejecting our responsibility for our effects on nature, so it follows that there must be a way to accept that responsibility that is not arrogance, not pride, and not sacrilege.

The “Do not play God!” principle is never used to make people do something, only to stop doing something. The principle commands us to let nature take its course. “Do not play God!” might be said, for example, to a mother considering surgery for her unborn fetus in order to correct a heart defect, remove a tumor, or prevent hydrocephaly. The mother is being told to let nature take its course. It may be argued that the course of nature represents the will of God, and its acts are said to be the acts of God (the phrase “acts of God” still serving as legalese for natural disasters). In short, doing something about the fetal defect is sinful arrogance, while doing nothing is virtuous humility. The objection to this is logical: the distinction between doing and not doing something is purely verbal. Therefore, even when we choose the course of what we take to be inaction, we are playing God just the same. The mother who refuses fetal surgery thereby chooses to bring an unhealthy baby into the world. Either way, she plays God. There is no getting away from it. From a mainstream theological perspective, every voluntary action or inaction (or “forbearance,” as inaction is sometimes termed) is an exercise of one’s God-given gift of free will, which is precisely the power to determine, if in only a small way, the course that creation will follow. To have free will is to be given responsibility by God for the course of events insofar as they are affected by one’s own choices. God has assigned us a role to play in the unfolding of the universe. We are, to put it poetically, assigned the role of small-g gods. The question is not whether to play God, but what sort of god one plays.

This being said, we must hasten to recognize that the warning not to play God is generally given when it seems the responsibility in question is too large to handle. This might be sound advice, regardless of any logical or theological flaws in its expression. Someone who is not a surgeon should not take responsibility for taking out someone’s appendix, for example. This, we should agree, is correct: We should not take on responsibilities that are beyond our capacities. On the other hand, we must realize that what is or is not too large is a complex matter that calls for a judgment, and that the judgment cannot always be avoided or averted. We are responsible in part for the state of some of Earth’s rivers, forests, and fields. What we do or do not do affects them, their natural inhabitants, and their (geographical or eco-functional) neighbors, too. What should we do? We cannot avoid our responsibility at this point. No matter what we do or do not do, we will produce effects that are under our control. It would be wisest, then, to accept out responsibility.

Fortunately, the proponents of global warming theory support this thesis, since it is presupposed by what they argue. They argue that we are responsible for a catastrophic warming of the climate and then conclude that we must stop doing whatever we are doing that is causing the catastrophe. As we saw in Chapter 6, this argument is not above criticism. Nevertheless, it presupposes that we can affect nature for the good as well as the bad. It urges us to take control and assume responsibility for the climate. So whether the argument is sound or unsound, its supporters grant this thesis.

- Neihardt 1975, p. 6. ↩

- Standing Bear 1933, p. 192. ↩

- Ibid., p. 248. ↩

- The history of modern science clearly shows its close relationship with technology from the outset, as, ironically, much of White’s own scholarship shows. It is no accident, for example, that Galileo’s great scientific breakthrough was based largely upon technological breakthroughs in lens grinding and telescope design that occurred in the Netherlands. It is no accident that both he and Newton contributed to further advances in telescope design through their scientific investigations into optics. Indeed, this pattern of mutual inspiration and support between technology and science is undeniably one essential element of the historical rise of both of them. ↩

- When Newton comes across problems that his physics does not explain, such as why the universe is not collapsing under the force of universal gravitation, he simply invokes the wise and mysterious ways of God, who placed the stars so far from each other that their gravitational forces were insignificant, at least during the brief lifetimes of such finite creatures as us. ↩

- The second law of thermodynamics, that entropy must always increase, is behind this fact. Organisms have to take materials from the environment to use in their life processes, and when these materials are returned to the environment their entropy is increased. For example, the food we eat is returned to the environment in a degraded form; that is, its entropy has increased. Organisms locally decrease their own entropy by increasing the entropy of their environment. Universal recycling, the recycling of all of the materials required for human life, would require that we magically decrease the entropy of our waste materials so that they are suitable for re-consumption. Put somewhat differently, universal recycling would require that the human economy become a perpetual motion machine. However it is put, universal recycling is simply impossible from a physical point of view. ↩

- Aristotle distinguishes the sorts of truth we can find in ethics and meteorology from the sort we can find in mathematics and basic physics. Whereas the latter may provide us with universal and exceptionless truths, the former yield at best only “truths for the most part.” The concept of type truths that I am employing here is, I believe, coextensive with Aristotle’s concept of truths-for-the-most-part. In any case, I follow him in thinking that the most important truths we seek within the field of values are not exceptionless, but nevertheless are really true. ↩

- The rationality of the emotions (or the lack thereof) is a topic that we cannot delve into here, but many excellent philosophical studies are available. A brief sense that the concept at least makes sense can be gotten from the observation that it would be irrational to love someone for the harm they have done you, or to be angry at someone for being good. Rationality is a concept that embraces not only logic, but values and feeling as well. ↩